Reviewed by Charlotte Pence

Marilyn Kallet, author of fourteen books, opens her anticipated selected poems with “Jonah on Oprah,” a dramatic monologue that epitomizes how through wit, rhythm, and imaginative metaphors her poems arrive at insight: “I’ve lived through gut-wrenching / remorse, got swallowed up by it. // Now I understand I can’t run / from my problems.”

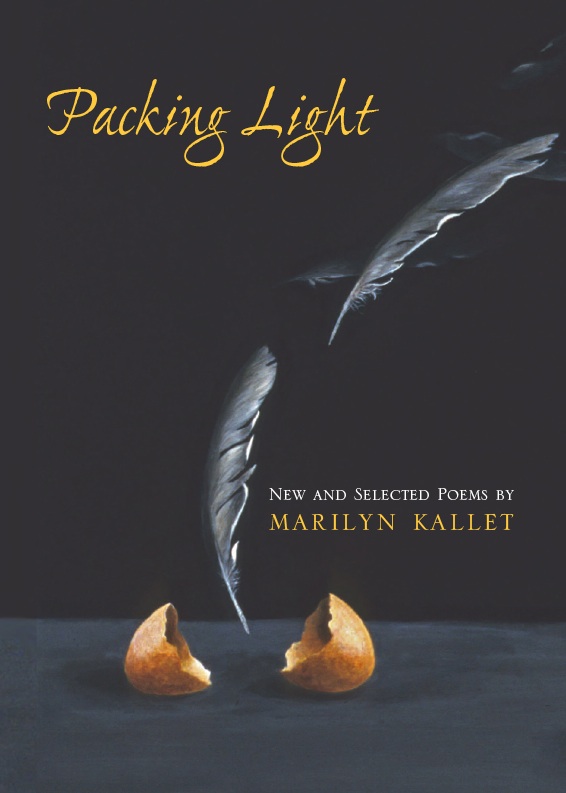

As this poem indicates, Packing Light: New and Selected Poems (Black Widow Press, 2009), is simply impressive, not only in its range, but in its craft.

From Theresienstadt to a New Brunswich flophouse, from the Garonne river to Jones Beach, from Pinnochio alongside pepper spray, the world within Packing Light teems with diversity, fullness, and a fierce insistence on including all aspects of one’s life that other poets would shy away from or discount.

This wide-armed approach is shown in “No Sale” where Kallet asks: “How would a Jewish girl/ sell her soul to the Devil?/ Reformed don’t believe / in Beelzebubba. // Now Robert Johnson, he / had no such trouble. / You know the tale/ how the bluesman / sold his soul at the crossroads // for a lifetime of hot-lick guitar.”

Not only do the lines delight on an intellectual level, but they croon with sound repetition, from the short “u” in “trouble” and “beezlebubba” to the alluring repetition of “s”s beginning with “bluesman” down to the “crossroads” that make the reader hold out those words as if in debate with the speaker to linger at the crossroads as well.

Kallet’s poetry operates not only through arresting juxtapositions, but through trusting sensual experiences such as the poem’s sounds to add another layer of meaning.

While some poems reside in the speaker’s inscape, that interior where poets wrestle with their conflicts, Kallet also complicates her poems through other characters.

Her poems are filled with memorable people like the mother in “No Makeup” who responds to her daughter’s ultimatum that she’d rather die than marry with “Then die;” to Marco at Bendel’s make-up counter who says, “Make-up can only do so much;” to Monsieur Moreau who eats his leek soup and remembers when the Paris police took away the Jews: “‘Les juifs.’ He giggled.”

Kallet’s stanzas often pivot on a stray piece of dialogue that serves as a counterturn. For example, in one of her new poems and one of her best, “Questions After the Poetry Reading,” the poet is giving a reading in Poland and afterward confronted with: “I expected your words to be more spiritual.”

This comment, as the dialogue often does, leaps the poem into a new direction ending with: “In a country steeped in the blood / of three million Jews, / what would it mean to be / ‘more spiritual’?”

While many readers lament today’s trend of flabby freeverse, Kallet’s readers will encounter no such fat.

As her selected works show, an openness to subject matter is honed and hardened by an allegiance to rhythm which for many of Kallet’s poems results in short lines syncopated with skat-like stressed beats. Consider these lines from “Two More Gorillas Send from Chicago”:

This ode’s for you, Bengati

And Jelani, newest boys

At the Louisville Zoo.

I don’t blame you

For scrapping with that

Bully, JoJo, mob ape

From Chi….

This mastery with the short line is evident in her early poems as well such as in “Come:”

“Come and cull the blossom / With your tongue. //We could climb like roses.”

Kallet also hones her lines by sometimes using a loose pantoum, a Malaysian form that builds momentum through repetition such as in “Goodbye, Deep France,” “Today the River,” and “Amiable.”

Previous reviewers such as Andy Brumer have acknowledged the traditions that inform Kallet’s work such as: “Williams’s comfortable and lapidary vernacularism, the confessionalist’s self-examination and exposure, the Beat’s leftist stance, spiritual howls and longing for transcendence” (13).

Yes, no reader can mistake the modern and post-modern strands that inform her poetry similar to the DNA’s double helix, yet another ancient mode informs her work as well, that of odes.

Horace’s odes, which tend toward the personal rather than public, and Neruda’s elemental odes which praises the everyday represent the dominant mode for many of her poems.

Granted, titles like “Ode to the Open Window” clearly point to that tradition, but more prevalent are poems that insist on blessing – especially and exactly those topics that are difficult to bless. Consider these lines from “Even this”:

Blessed be the rumors and lies

That snap at my feet like wild dogs,

Even these belonged to somebody.

Blessed be the way they grow quiet

And sleepy over time.

Blessed be the strength to ignore them.

The ability to turn dross into gold is exactly the type of alchemy poets do. It is Kallet’s Whitman-like embracing of pain and loss, be it the Holocaust, a mother’s death, or simply those times where reality replaces dreams, that so fiercely connect readers with Kallet’s poetry.

She has her following, to be sure, and part of her reader’s commitment to her work stems from Kallet’s commitment to blessing this world we have, not the one we wish it were, but the one in which we must live and learn to love.

4 comments so far ↓

Nobody has commented yet. Be the first!

Comment