Interview with Kremena Todorova and Kurt Gohde by Katerina Stoykova-Klemer

Kurt and Kremena at the opening reception for DISCARDED: Lexington

Photo: Rich Copley/Lexington Herald-Leader

Kremena Todorova teaches American Literature as well as classes that ask students to meet and work with their neighbors face to face. Born and raised in Communist Bulgaria, she continues to draw inspiration for her art and teaching from Timur and his commitment to community. She became an official American on December 10, 2010.

Kurt Gohde teaches Studio Art at Transylvania University and makes art to invite conversations about contemporary social issues, from marginalized sexualities to the experience of homelessness. Recently, he has become newly invigorated by plans to reseed the clouds over Kentucky with meat, in loving memory of the Kentucky meat rain of 1876.

In addition to drag queens, Kurt Gohde and Kremena Todorova like to photograph discarded couches, roadside attractions, and all things found on the peripheries. Currently, Gohde and Todorova are working on The Lexington Tattoo Project, a public artwork that has already spread the words of a poem, through permanent tattoos, on the bodies of 247 Lexingtonians. They have exhibited their collaborative work in Lexington, KY; Venice Beach, CA; Indianapolis, IN; Oneonta, NY; and San Antonio, TX.

What is creative disruption and why do we need it?

We think of acts that refresh our vision and prompt us to re-engage with our physical and social environment as creative disruption. Creative disruption re-energizes us by refreshing what appears ordinary and unchanging; it can prompt us to see realities that were hidden before; it can make us reach out to people of whose lives we were not previously aware. In short, we think that interventionist art and creative disruption are synonymous. When pressed to label ourselves, we sometimes call ourselves interventionist artists.

Photo: Kurt Gohde and Kremena Todorova

How do you come up with ideas for your projects?

Our artworks are born from ongoing conversations the two of us have, from ideas and people both of us find irresistible, from things we are passionate about. For instance, we ended up building the world’s largest mustache cup because we could not get over our shared fascination with mustache cups and because Transylvania University, where both of us teach, owns the world’s largest collection of mustache cups. Both of us knew we would have to make art based on mustache cups sooner or later. We ended up doing just that in the summer of 2010—we were that impatient!

Photo: Kurt Gohde and Kremena Todorova

Do you have more ideas than you could possibly bring to completion? If so, how do you choose what to work on? What happens to the “leftover” ideas?

Absolutely! We have a number of documents saved with ideas to pursue in the future. We start these files and then forget about them, because we trust that if an idea is compelling enough, it will haunt us into making something of it, that we won’t forget about it. This is how we end up deciding what to work on: a few different ideas gradually germinate into an artwork we cannot resist and we begin working on it.

For instance, we have both long been interested in 3D graffiti (there was a period of time when Kremena kept telling everyone she was going to become a graffiti artist), in artworks that use the human body as a canvas, in community-based projects. The Lexington Tattoo Project was born from all these interests and bears obvious connections to each of them.

As to the leftover ideas, they sit in the back of our minds, until they grow into something bigger and better. We are both fascinated by maps. A few years ago we began talking about different things that we could map: things like habits and habitats that we find curious. Then DISCARDED and The Lexington Tattoo Project happened. Who knows, maybe one day we will create maps based on all the people we will have photographed as part of these other artworks.

How are the projects accepted by the participants as well as the general public?

As far as we can tell, people really enjoy our collaborative artworks. We believe that this happens because most of our projects depend on participation. Indeed, the distinction between audience and participants is frequently blurry: participants become part of the audience as they observe other participants, while simultaneously engaging with these participants and giving the artwork new life.

Though we do not typically begin a new artwork with an awareness that people love to connect with others, that they need these kinds of relationships in order to feel fully engaged with their neighborhoods and cities, we frequently realize that this is the main reason the general public responds so favorably to our work. By feeding our love for people and connections, we help satisfy others’ needs for the same.

Kurt and Kremena with participants in the Lexington Tattoo Project

Photo: Mick Jeffries

How did you decide to collaborate together? What are the rewards and the challenges?

We began working together in the spring of 2008 as we team-taught a class called “Community Engagement Through the Arts.” When one of our class visitors, Sarah Milligan of the Kentucky Oral History Commission (KOHC), told us that KOHC gives out a number of grants each year for oral history projects, we decided to apply for a grant to work with the community of drag queens and kings who have called Lexington their home (Kurt had previously photographed some of them so we had an in with that community, so to say). This is how Passing was born: as a series of 20 oral histories, which preserve the stories of one of Lexington’s overlooked communities.

We find many rewards in working collaboratively—we share all the responsibilities inherent in community-based artworks, we energize each other, we bring our different “areas of expertise” into our shared work—but we think that the biggest advantage to working together is that we never give up at the same time. Whenever one of us feels exhausted by the amount of mental and physical energy that goes into our work, the other one is there to keep things going.

Kurt, Kremena, and Scott Shive, Interview with The Herald-Leader

Photo: Rich Copley/Lexington Herald-Leader

As far as challenges, our single largest challenge is that people do not always realize that we own every part of our projects together, that we collaborate on each bit. Because Kremena teaches American Literature, people tend to assume that she is in charge of the writing that goes into any of our artworks. By the same token, Kurt’s background in Studio Art leads many to believe that he is the photographer and the maker.

We would have become bored by our art a long time ago if we divided our work along these kinds of rigid disciplinary lines. Learning to create photographic portraits, to write beautiful words, and to communicate with people who rely on us to tell their stories truthfully are skills both of us have had to learn. These are also some of the biggest rewards of our collaborations.

You two were listed in a Lexington Herald Leader survey among the top most influential people in Lexington, KY. How did that make you feel?

We were totally surprised—we had no idea we had been nominated—and flattered, of course. We were listed right next to Lexington’s Mayor Jim Gray, a long-time friend and supporter. It was absolutely an honor to be part of a group of politicians, policy-makers, leaders, and arts professionals who were deemed influential.

We were the only conceptual artists included: were glad to find out that people are noticing and appreciating the community-building aspects of our collaborative works. We were also the only pair of people to share a single voting box—this enabled us to joke about a two-for-one deal.

Many of your projects are connected to the place you live in – Lexington, KY. What can you tell us about this place and your relationship with it?

We arrived in Lexington at different times. Kurt got here in 1998 to teach Studio Art at Transylvania University. Kremena joined the Transylvania faculty in 2005 as part of the English Program. By the time we began teaching and working together in 2008, Lexington was undergoing a revival, thoroughly energized by people’s desire for a culture of walking, biking, and building a better city through communal efforts.

Unlike other places the two of us had previously lived, Lexington was generous with newcomers. Each of us soon felt rooted within the local community (in fact, Kremena’s chosen words as part of The Lexington Tattoo Project are “deep roots”!).

In the years since we began working together, we have come to appreciate our fellow townspeople—community activists, artists, neighbors, do-gooders, and plain ordinary folks who are all amazing—and to rely on them for all kinds of support. We expect them to tell us just what they like in our work, we hope that they will sit on shabby couches when we ask them to, and, more than anything else, we trust that they will be moved by the same ideas and images that move the two of us. So far, we have been very lucky. We feel embraced by our community: a community the two of us are committed to.

Tattooing the tattoo artist

Photo: Mick Jeffries

Tell us about The Lexington Tattoo Project. What has been the reception? What else should we expect to see as a follow up?

At the core of The Lexington Tattoo Project is our love for Lexington and its people. Back in May 2012 we asked Lexington-based poet Bianca Spriggs to write a poem as a love-letter to Lexington. Though Bianca responded that her relationship with the city is more complicated than straight-ahead love, she wrote a beautiful poem titled “The _________ of the Universe: A Love Story.” The two of us then designed a layout for the poem including a background image—which is made of three kinds of circles—that will remain a secret until the fall.

This background image is divided, like a puzzle, among all the tattoos (each tattoo is created from one or more words of the poem) and therefore makes each tattoo distinctive and recognizable as part of this project. Most of the tattoos were completed in January by Robert Alleyne and Jay Armstrong at Charmed Life Tattoo Studio in Lexington. We are almost done photographing each healed tattoo: a total of 252 people became part of this project with a tattoo.

Enrique Turner’s “of the Universe”

Photo: Kurt Gohde and Kremena Todorova

The Lexington Tattoo Project surpassed all of our hopes and expectations as soon as we advertised it on Facebook. To begin with, we had hoped to find 100 people willing to participate by getting permanent tattoos. The actual number of would-be participants swelled to over 200 before we even considered how to deal with a community-based artwork that received far more community support than we were expecting, than we needed. We ended up with 252 participants and a log waiting list. (In fact, we are still receiving inquiries about available tattoos and emails from people who regret not finding out about this artwork in time to sign up for it.)

We never anticipated all the ways in which folks would make the tattoos their own. More than 30 romantic couples (both same-sex and heterosexual) got tattoos together, some of them splitting phrases. We know of 5 mother—daughter pairs and 6 mother—son pairs (in one case it’s a mother and her 2 sons) who got tattoos.

There is a family of 5, with each member of the family getting a tattoo. Participating in The Lexington Tattoo Project was many people’s way of affirming personal connections, in addition to the more obvious communal bonds at the heart of the artwork. Additionally there are incredible stories behind people’s choice of words, stories that connect participants with their tattoos while only sometimes connecting to the words’ meaning within the larger poem.

Kristin Combs and George Birk’s “The Knock Knock Joke of the Universe”

Photo: Kurt Gohde and Kremena Todorova

What to expect next: a video of Bianca reading the poem while the words of the poem scroll as tattoos—we will show this for the first time at a big party on November 15, 2013, the opening night for PRHBTN (Lexington’s annual street-art festival); a book that will highlight some of the personal stories behind the tattoo choices and will include an image of every single tattoo—it will be ready in early February, on time for Valentine’s Day 2014; The Boulder Tattoo Project, which is well on its way; The Miami Tattoo Project, which we expect to begin in the late summer/early fall 2013. We are also working on funding a documentary about all the Tattoo Projects and the people and stories that become part of them.

What is DISCARDED? How did this project start and where did it take you?

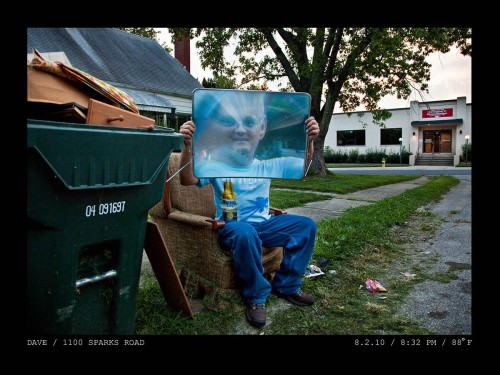

DISCARDED began in the late fall of 2009, during a season when discarded furniture abounds on curbs throughout Lexington. Each of us spotted a piece we wanted to photograph: a green plaid sofa precariously poised on a boxy television set, a golden brocaded chair oddly out of place in front of a house known to neighbors as “the hooligans’ house.”

Each of us wondered about the stories connected to these pieces, about the people who had until just recently sat, lounged, or curled up on them. We knew that we could capture some of these stories by asking the owners or their neighbors to sit on the cast-away furniture. We decided to create portraits of these people, our neighbors, on the well-worn sofas and chairs. We believed that by doing so we would capture a single moment in the furniture’s life.

We took our first photograph on January 8, 2010. Because the temperature had finally climbed above 20 degrees and because the sun was shining, Billy agreed to sit on the sofa he and his girlfriend had dragged out into the snow in anticipation of their new living-room set. Prior to meeting Billy, we had been repeatedly turned down by a houseful of college students who said 15 degrees was too cold to sit on the grey sofa they had put on the curb.

Billy, DISCARDED: Lexington

Photo: Kurt Gohde and Kremena Todorova

Afterwards we had more success than rejection though bed bugs gave pause to many of the people living in Lexington’s poorest neighborhoods. Though we began with the intention of capturing the stories that lived within the old pieces of furniture, we soon realized that our images amounted to something more: a collective portrait of a year in the life of Lexington, KY.

This portrait includes urban hipsters, mechanics, mothers with infants, suburban dwellers, traditionally-defined nuclear families, college students, cousins, brothers, and friends. It includes dogs, tattoos, Mardi Gras beads, empty beer cans, old teddy bears, and all the things that create the texture of our everyday lives. It includes our neighbors, even those frequently hidden from view by entire neighborhoods labeled as “hooligan.”

Dave, DISCARDED: Lexington

Photo: Kurt Gohde and Kremena Todorova

We took our last DISCARDED picture in Lexington on January 8, 2011: another wintery day 365 days after photographing Billy in the snow. We exhibited the full set of 277 images—along with poetry inspired by them, a song written by Vandaveer for the show, discarded furniture, and silver wall drawings—at Land of Tomorrow Gallery in Lexington in February 2011.

Since then we have traveled to photograph discarded furniture and the people who live near it in a variety of cities throughout the U.S.: Los Angeles (2011), Indianapolis (2011), New Orleans (2012), and San Antonio (2012). We plan to create two more city-specific collections before we call DISCARDED: USA complete. So far, DISCARDED has taken us to little known neighborhoods in San Antonio, to a Vietnamese immigrant village in New Orleans, to Los Angeles neighborhoods that remind us of our own neighborhoods in Lexington.

Most importantly, DISCARDED has enabled us to appreciate these different cities and the people who live in them, regardless of our preconceived ideas about them. This is ultimately what we hope for each of the exhibitions we’ve had in each of these cities: that it will enable viewers to get to know and appreciate the tremendous diversity of the lives that surround them, even if they are not always aware of them.

Liquann, Paul, Kiev, Asia, Delilah, Crystal, Janeim, Timmy, Montas, and Jakel, DISCARDED: Lexington

Photo: Kurt Gohde and Kremena Todorova

Tell us about Good Morning: The American Inn Project? What is the symbolism? How did you decide to use music by Vandaveer?

We began Good Morning: The American Inn Project as part of a class we were preparing to teach together in May 2011, “Creative Disruption.” One of the course requirements for students was to stage a daily disruption of a social norm or expectation. We decided that this assignment—which we did alongside our students—was an ideal opportunity to use the abandoned sign for a motel that had been demolished many years earlier.

Kurt had seen The American Inn sign on one of his couch-scouting trips in Lexington about a year before “Creative Disruption” began. He recognized the tremendous potential of the sign and, before anyone else had a chance to seize on this potential, the two of us rescued the letters of the sign, which still dutifully announced “_ightly & _eekly rates.”

Kremena and Kurt working on Good Morning: The American Inn Project

Photo: Kurt Gohde and Kremena Todorova

Shortly before we began work on Good Morning: The American Inn Project, Kremena passed the test for citizenship and all things American were of special interest to her (not to mention her focus on American Literature in the classes she teaches at Transylvania University). Also shortly before we began work on this project, we had both been listening to Vandaveer’s latest CD and enjoying a song called “Good Morning.”

This song, which opens with the question “how did you sleep,” seemed particularly suited for an artwork connected to a roadside motel. We saw the potential in this abandoned motel sign for sustained, albeit one-sided, communication with the drivers on New Circle Road (one of Lexington’s major motorways). We always enjoy the idea of making artwork that masquerades as something completely different: in this case a motel sign broadcasting seemingly random messages to passersby.

So in the course of five months we visited the sign daily, changing the letters to spell out a bit of Vandaveer’s song, capturing 561 photographs, and becoming the adopted family of a feral black-and-white cat. The resulting video artwork chronicles a summer-long dialog between Vandaveer, by way of our abandoned motel sign, and the motorists making their daily commute along New Circle.

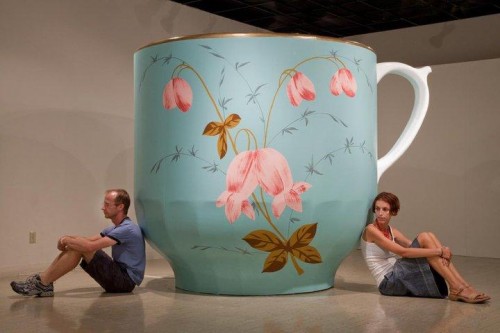

I had no idea mustache cups existed, but I’m thankful to know. Tell us about Royal Dandies.

We fell in love with the aesthetics and ambiguities of mustache cups as soon as we saw Transylvania University’s amazing collection of them—the world’s largest collection. Invented in 1830 in England, these heavily ornamented and gilt cups were created to protect the carefully styled facial hair of men from the steam that would rise to their lips while they were drinking hot tea.

Four years before the invention of mustache cups, in March 1826, the funeral for Emperor Alexander I in Saint Petersburg, Russia included the world’s largest funeral procession for a faked death. Because we had long enjoyed a book in Transylvania University’s Special Collections (Procession Funebre de feu S.M. l’Empereur Alexandre I) for its hand-painted and labeled images of every person, flag, canon, carriage, and horse that was part of this procession, and because we were growing more fascinated with mustache cups, it was natural for us to find connections between these two compelling stories, stories filled with formality and rituals that no longer sustain us.

Four mustache cups from Transylvania University’s collection of mustache cups

Photo: Kurt Gohde

Once we discovered, through research, a surprising connection between these two stories, we simply had to make an artwork about it:

• Feodor Kuzmich, a mysterious and quiet monk who appeared in Krasnoufimsk, Siberia, ten years

after Alexander’s funeral, without a history but with a full beard, is believed by historians to have been the Emperor himself, spending the rest of his life in humble circumstances and quiet prayer. The single decorated object the monk possessed was a mustache cup: gifted to him by Queen Victoria of England, Emperor Alexander’s god-daughter.

For Feodor Kuzmich, for Alexander I, and for Transylvania, we built the world’s largest mustache cup: a cup that invites visitors to sit inside and share stories of wonder. We called this artwork Royal Dandies, in honor of Emperor Alexander I and all men who could afford to drink their tea from mustache cups.

Kurt and Kremena with Royal Dandies

Photo: Kurt Gohde and Kremena Todorova

As far as I know, Passing was your first project, and you have been working on it for years. Please speak about the idea, the effect of the project on the community, as well how this experience changed your lives.

Passing, our first collaborative artwork, began in the spring of 2008 when the Kentucky Oral History Commission funded our grant proposal to record twenty oral history interviews (a second grant a year later supported seven more interviews) in order to preserve stories from and document the lives of the drag queens and kings who have called Lexington home. We started taking photographs a few months later to create more layered representations of the performers who were part of our project.

Since then we have photographed the queens and kings on and off stage, as they sew outfits, when they are applying makeup, and as they prepare to perform. We have visited them in their homes, joined them at fundraising events, photographed them at national pageants, and followed their performances in six different Lexington bars. Throughout this time we have also been writing short vignettes inspired both by the stories we heard during the interviews and by the individual performers we have watched on stage.

Passing: All-American Goddess Pageant, 2012

Photo: Kurt Gohde and Kremena Todorova

Now in its fifth year, Passing has become an ongoing tribute to Lexington’s queens and kings, a tribute that also aims to remove some of the social barriers surrounding the gay community in Kentucky. We continue to give presentations about Passing—both for university classes and for conference audiences—locally, nationally, and internationally.

We hope that every oral-history-interview story we share challenges negative stereotypes about the performers and their lives. We trust that these stories—narratives about struggling to gain parental and social approval, about coming out to siblings, grandparents and neighbors, about going on stage for the first time—reveal a lot more similarities than differences in how we all live our day-to-day lives.

Passing: All-American Goddess Pageant, 2012

Photo: Kurt Gohde and Kremena Todorova

Though it is hard to measure the effect of Passing on the larger Lexington community, we are aware of two things. First, the Transylvania students who attended any of the drag shows we helped to host at the university (we helped host drag shows in 2009, 2010, and 2012) absolutely loved the shows, both for the visual pageantry and for the acceptance of all sexualities that marks any drag performance.

Second, we have made lots of friends. We think that this is inevitable because of the powerful connections forged through shared stories and a shared understanding of lives lived on the social margins. And so it’s hardly a surprise that people we met as part of Passing have since been involved in every other artwork we’ve made in Lexington.

Yes, our lives become richer with every community-based artwork we create. We meet so many good people—people who mark our lives and our thinking permanently. This may be another reason we continue to make work that directly engages our community.

What is next for you? Is there another exciting and original project in the works?

Though we have ideas for new artworks, both of us feel that we need to see The Lexington Tattoo Project (and all the companion Tattoo Projects), DISCARDED, and Passing through to completion before we embark on something totally new. Each of these multilayered artworks comes with a tremendous sense of responsibility towards the stories of the people with whom we work. Giving public voice to these stories is a priority, before our next adventure can begin.

Kurt and Kremena photographing for DISCARDED: New Orleans

Photo: Kurt Gohde and Kremena Todorova

2 comments so far ↓

Nobody has commented yet. Be the first!

Comment