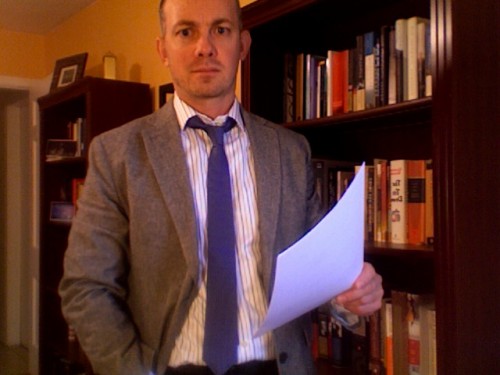

In addition to Public Republic, Kevin P. Keating‘s fiction and essays have appeared in a number of literary journals, including The Ampersand Review, Identity Theory, Exquisite Corpse, Perigee, Whiskey Island, Juked, The Mad Hatter’s Review, Wordriver, and many others. The Natural Order of Things is his first novel. He currently teaches English at Baldwin-Wallace University near Cleveland, Ohio. He owns a shih-poo named Coconut and enjoys bicycling.

Here we are, less than a month away from the release date for your first full-length book, “The Natural Order of Things”, a novel comprised of 15 interconnected stories about the lives of several students, teachers, priests and the staff at a Jesuit prep school in an industrial city in decline.

How would you describe the path that led to its release? What were some of the challenges you encountered while writing and preparing it for publication?

Creating a longer work of fiction poses unique challenges for every writer, and with The Natural Order of Things I found myself on a somewhat convoluted path to publication, one that may have posed greater challenges than if I had written a more traditional novel. Rather than sitting down at my desk to compose one continuous story, I actually wrote, over a period of about four years, thirty separate short stories.

At some point I decided it was high time to gather the best of the bunch and try to market them as a story collection, but as I began the process of selecting stories for this hypothetical book, I noticed how certain thematic patterns seemed to emerge; it then occurred to me that what I really had on my hands was a “novel-in-stories,” or what one critic called a “web of life” story, in which one particular action is seen from the perspective several characters.

Each character views and interprets this central action in very different ways. I then began to eliminate those stories I found superfluous to the narrative arc while I added others. I ended up with fifteen stories that I thought worked well together. I then arranged and rearranged the sequence of these stories.

During the process of assembling the book, I continually revised and workshopped each story. I like to use the wonderful website Zoetrope.com where writers comment on one another’s work, and I received some truly extraordinary feedback from dozens of perceptive readers. I also submitted each revised story to various literary journals, like Public Republic, hoping for editorial feedback.

All of this was a big undertaking, and it took me two full years, but after the crucible of revision, editing and workshopping, I finally had a complete manuscript that I felt was ready for submission.

Several of the stories in the book have been nominated for various prestigious awards, including the Pushcart Prize. Do you have a personal favorite among them? What made you decide for a looser structure of the novel versus the conventional form with a defined flow, beginning and end?

The looser structure was really born out of necessity. I felt that with a traditional novel I couldn’t get a fair hearing from the publishing world, which is bombarded each day by stacks of unsolicited manuscripts. My impression was (and still remains) that it is a virtual impossibility for any first-time writer working without proper representation and a proven sales record to get noticed by even the smallest, indie presses.

The competition is steep. So for me the short story form became a more realistic path to success. My philosophy was this: if I stuck to the short story form I could hone my craft and submit my work to a variety of literary journals open to new voices. In this way I was able to build a kind of “track record” that allowed me to demonstrate to publishers that my work had enjoyed a certain amount of success.

As you mentioned, several editors nominated my stories for awards, including the Pushcart Prize and the StorySouth Million Writers Award. Accolades like this probably help when seeking a publisher for one’s book. My efforts were validated when Publishers Weekly decided not only to review my book, but to give it a coveted star review.

As for my favorite story, well, I’m not entirely sure I have one. I hadn’t looked over the manuscript since I completed it (April 2011), but suddenly it was time to begin the process of copyediting with my publisher, and I had to revisit the stories again. I thought I would cringe at my past work, the way some actors are said to cringe when they watch their performances on screen, but I feel that, overall, the writing has held up pretty well after so much time.

I always liked “In the Secret Parts of Fortune,” which is my sly homage to Shakespeare, especially the plays “Hamlet” and “Macbeth.” I also like “Hack,” which is my “Nabokovian” story in that I play word games like anagrams and acrostics. “The Distinguished Precipice” is my nod to the poetry of Emily Dickinson; it’s the darkest of the stories, but I think the drama of it is quite effective.

How can the book be purchased? Have you planned any special events for the release date?

The book can be purchased directly from the publisher, Aqueous Books, and pre-orders are now available. Beginning November 30th the book will be also available for purchase through online retailers like Amazon and Barnes & Noble, which is especially convenient for those people who prefer to use an e-reader like the Kindle or the Nook.

In terms of special events, I am having a book launch party on December 7th at Baldwin-Wallace University in Berea, Ohio where I have been teaching English for close to twelve years. I may do a couple of readings at independent bookstores in the Cleveland area, and I hope to participate in a reading next summer at the Market Garden Bar and Restaurant in Cleveland’s Ohio City neighborhood, which is run by the distinguished poet (and my cousin-in-law) Dave Lucas.

You’ve worked as a boilermaker, landscaper, painter, bookie’s apprentice, and beauty pageant judge, among other things. Do you think that the various perspectives these experiences have given you have in some way enhanced your writing? How does your personal life factor in your work?

The Natural Order of Things is a work of fiction, and everything in it is essentially a product of my imagination, but some autobiographical elements inevitably crept into its pages. One of the things that has interested me in life, and in fiction, is the idea of a person, or a character in a story, having the ability to drift in and out of two very different worlds.

For example, I come from a blue-collar, working class, industrial city, and I socialize with many people from this world. But I am also a writer and a professor of English, and I socialize with many people from this world. The people in these disparate social milieus rarely seem to encounter one another.

Very few pipefitters and boilermakers attend poetry readings or enroll in literature classes or take leisurely strolls through art museums, and very few poets work twelve-hour shifts in the steel mills and drink whiskey in the rough-and-tumble bars around shuttered factories. I have had the great good fortune to not only see both of these worlds but to live out the experiences unique to both, to work in oil refineries and to teach in lecture halls, to repair boilers in rendering plants and to discuss the novels of Cormac McCarthy with college students and fellow professors.

All of this is reflected in my book where the characters find themselves floating through these worlds and are inevitably affected by the experience of playing different roles, depending on the particular environment; some of the characters come from wealth and privilege but find themselves living suddenly and inexplicably in a notorious flophouse.

Fiction and essays – are these the genres you generally write in and would you consider other ones?

For me, yes, fiction and essays are the only two forms I would consider seriously. In my view poetry is a completely different medium, as is playwriting. It’s probably akin to the art world where you have people who strictly paint or focus on sculpture or pottery or assemble these extraordinarily avant-garde installations made from found objects.

Some writers, like John Updike, have been able to successfully work in both mediums (poetry and fiction). Cormac McCarthy is noted as both a writer of fiction and plays. But for the most part I think writers stake out their territory early and stick with it. Some writers of fiction even adhere to specific forms. Jorge Luis Borges, to my knowledge, only wrote short stories and never dabbled in longer forms like the novel.

I know he wrote poetry in his younger years, but as he got older he focused more and more on his stories, some of which were a peculiar story-essay hybrid, or perhaps one should say “fictionalized essays.” H.P. Lovecraft was primarily a writer of short stories and only attempted to write a couple of novellas. I would like to try my hand at a traditional novel one day, but I worry that I might lose interest in a single, continuous storyline.

What difference does the choice of a Jesuit school as the main place where the action in The Natural Order of Things takes place make? How about the dying industrial city?

Being a Jesuit college in a declining city itself, my own Alma Mater nevertheless strives for transformative education and instilling high moral standards in its students, but seems to be faced with the double danger of students that are either too rebellious or too apathetic to allow these standards to impact them. How is that in your novel?

I experimented with a few different settings for this book. For a long time I toyed with the idea of setting The Natural Order of Things at a university where, I initially believed, students and professors might actually get involved in deep, metaphysical discussions, but as a college instructor I’ve come to the conclusion that there is something very artificial about higher education in this country and about the college experience in general.

There is an old joke that a philosopher is someone who shows up to work each day wearing a sport coat and a tie, carrying a briefcase, and philosophy is just something he does to earn a living from nine in the morning until five o’clock at night. The same cannot be said of a Jesuit priest who never ceases to be priest at the end of the workday. In addition to this, I think the relationship between teachers and students is much more intense at the high school level.

At the university level students are, for the most part, left to their own devices and will either succeed or fail on their own; they’re now at an age where they must assume a great deal of personal responsibility. At a private high school, however, students look for mentors, and teachers are expected to play a much more active role in the development of their pupils.

But in the end the biggest reason for my decision to set The Natural Order of Things at a Catholic high school is because it afforded me an opportunity to discuss these big, metaphysical issues in a modern context. We have what amounts to a sort of archaic, almost medieval, world with a tradition dating all the way back to antiquity operating within the context of a modern, post-industrial society.

The Jesuits tell students that God exists, but these same students, living in a big city, are simultaneously exposed to people who hold contrary views based on startling, new scientific discoveries which only seem to confirm humanity’s insignificance in the unimaginably vast cosmos. This is yet another example of two worlds colliding, and it goes along nicely with the thematic idea of blue-collar types mingling with educated elites, except now we have the religious and the secular worlds colliding.

In terms of morality and behavior, I think the same sort of thing applies. The Jesuits insist on high moral standards, but many of the students in my book come from a world where they are surrounded by temptations of every sort. The characters must contend with all sorts of things that make different demands on them emotionally, psychologically and spiritually, and any simple answer, any platitudinous philosophy, is an inadequate way of dealing with tough realities and the sometimes insurmountable complexities the world presents to us each day.

Do you think the attitude of most of the inhabitants of the city in your novel who “would rather gamble on a human life than try to save one” is a global trend that can be found anywhere around us, or is especially characteristic of declining urban spaces?

I think any work of fiction, if it’s going to be successful and resonate with readers long after they’ve finished reading it, must address some universal human concerns and behavior patterns. No doubt there are people out there who would rather gamble, or perhaps exploit, other human beings for personal gain rather than attempt to help them in some way.

In my hometown, Cleveland, we have seen the rise of an unsettling new socio-economic phenomenon, sometimes labeled “post-colonialism,” in which a few multinational conglomerates and big businesses come from outside the city (and occasionally from outside the country) and offer jobs to an unskilled workforce for very low wages, often without benefits. The old industrial jobs that used to pay good wages and allowed people with high school degrees to move into the middle-class suddenly vanished.

The steel mills and automobile plants closed down, and this had a very destructive effect on what was once the sixth largest city in the United States. I think many residents came to see themselves as being bullied and exploited by cynical business leaders who were motivated by profits. Cleveland in recent years has made an extraordinary comeback, but this was the direct result of private-public partnerships and cannot be credited solely to the free enterprise system.

Cleveland, perhaps the capital of what is sometimes derisively called “the Rustbelt,” was an area of the United States that had to deal with the effects of a long lasting recession before other areas. It has had a profound impact on the collective psyche of the people, and this, too, is reflected in the characters in my book. When people are poor and desperate, they may behave in ways that are not so admirable.

For you, what qualities make the most powerful stories?

I’ve always believed that the most powerful stories are those that blur the boundaries between genres, that refuse to abide by the rules of one particular literary world–comedy, tragedy, history, romance. As a devotee of Shakespeare, I know that scholars have invented the term “problem play” to describe the bard’s work, particularly his later efforts like Measure for Measure and The Winter’s Tale (and sometimes even Hamlet).

The reason these plays are considered problematic is because they cannot be easily or neatly categorized as comedies or tragedies. But I think the term “problem” applies to virtually all of Shakespeare’s plays. There are many tragic and nightmarish aspects to an otherwise traditional “comedy” like Much Ado About Nothing. And how is one supposed to regard a play like King Richard III? Is it really a history? Political intrigue seems a more appropriate description.

And what about Richard himself? Is he a monster or a clown? After all, he is both devious and witty. Is Macbeth a protagonist or an antagonist? At the beginning of The Natural Order of Things I quote from my favorite of Shakespeare’s oeuvre, the King Henry IV plays. What are we to make of these dramas? Are they, like King Richard III, “histories?”

This is incredibly comedic material, and Falstaff is unquestionably a figure of fun, but at the same time he is one of the most human and endearing characters in all of Shakespeare. And even though Prince Hal may be the protagonist of these plays, he’s also incredibly cynical, a Machiavellian prince if ever there was one (a theme that is given full voice in Henry V). My favorite works of fiction follow this “problematic” formula. What are we to make of Vladmir Nabokov’s infamous madman Humbert Humbert in Lolita?

Is he simply a sexual deviant? I don’t think so. And what of Cormac McCarthy’s characters, especially the Judge in Blood Meridian who seems to be both a god and a devil. He is at once a wise and erudite philosopher and a gun-toting maniac. I think any serious reader can go through many of the “great books” in just this way and take into consideration all of the psychological contradictions of the characters–the priest in Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory, John Self in Martin Amis’s Money, Ahab, Wakefield, Leopold Bloom. No one is entirely good or bad, and any work of fiction that pretends otherwise would strike me as disingenuous and boring.

You point to José Saramago as one of your favorite authors. Could you tell us more about why you like him and perhaps also whether you think it is vital for good writers to also be good readers?

José Saramago is the type of writer who doesn’t back away from unpleasant realities. I was profoundly moved by his novel Blindness, which must surely be regarded as one of the great post-apocalyptic visions of the twentieth century. Unlike many popular books that explore the demise of civilization (think of Stephen King’s The Stand or Frank Herbert’s The White Plague), Blindness isn’t a fantasy, it isn’t escapism, it isn’t the kind of thing you read for fun to forget your troubles and have a bit of a scare.

Saramago forces you to confront your worst nightmares, and perhaps more troubling still, he forces you to confront your own demons. Again and again in his work, he explores the more sinister aspects of society. In Blindness he seems to suggest that human beings have a natural tendency to form totalitarian systems of control where thugs, sadists and sociopaths will invariably take charge of things and harm the weak for fun and sport.

In The Cave Saramago focuses on the dehumanizing effects of crass consumerism, and in All the Names he focuses on the dehumanizing effects of the modern workplace. The other important thing about Saramago is that he is a challenging writer. His books are not “page turners.” He forces us to become better readers. We must pay close attention to every word and the subtle implications of each sentence. In a sense Saramago is a great teacher for the aspiring writer.

When it comes to writing, what do you think is more important – “natural” talent or discipline?

I suppose a bit of both are required. I wanted badly to become a competent pianist. For many years I tried and tried to play well, but I simply lacked the natural ability to be any good at it. But those people who are blessed with a gift for the piano will tell you that practice and self-discipline are absolutely indispensable to success.

George Gershwin, the composer of Rhapsody in Blue and Porgy and Bess, continued taking lessons throughout his adult life, and even conductors as accomplished as Daniel Barenboim and Leonard Bernstein have said that they practiced at the piano for many hours every single day. The same can be said of writing.

Most successful writers have a strict regiment, and they dedicate several hours a day to their craft. I recall reading an interview in which Peter Straub, a fine writer of “weird” fiction, once said that the imagination was like a muscle–from time to time it requires a strenuous workout; the more you use it, the stronger it becomes.

Do you think an author should do marketing for themselves and for their published works, or do you prefer leaving that to the publisher?

In the best of all possible worlds I would prefer to be a writer, not a businessman. I’m working with a small, independent press with limited means, and the simple reality is that I must do a lot of the marketing myself, that is if I want to sell more than a few dozen copies. I would like to reach as broad a readership as I possibly can.

But I must say the experience has been a positive one because it has forced me to learn a lot about the book trade. A writer, if he wants to attract readers, must solicit reviews, participate in interviews, attend readings, utilize social networking sites, organize book launch parties, and so on. There is no easy way to go about any of this. It takes a lot of effort and old-fashioned elbow grease.

Do you have an agent and do you think the figure of the agent is important to an author’s success, and what does success mean to you anyway?

Currently I do not have an agent, but I hope The Natural Order of Things will attract some attention and allow me to get my foot in the proverbial door of the publishing world. Maybe this will make my life a little easier, and I’ll be able to devote more of my time to writing rather than self-promotion, which I find a bit awkward.

What advice would you give to aspiring authors who would like to see their works published?

The formula for success is an old one: hard work, persistence, dedication, and lots of luck. Write every day and spend the majority of your time re-writing, re-writing, re-writing. Learn your craft, perfect your sentences. Read the great writers. Study the way they put their stories together.

When you’re confident you have produced your best work, and you have carefully edited it, then you can begin the process of submitting to various markets. But you must also prepare yourself for rejection and try not to get too discouraged. If you have confidence in your vision, and you are sure you have done your very best, you should find success sooner or later.

_________

Links:

- www.kevinpkeating.blogspot.com

- Purchase The Natural Order of Things here

4 comments so far ↓

Nobody has commented yet. Be the first!

Comment