An Interview with Artist Deborah Grigsby by Jasmina Tacheva

Photo: Deborah Grigsby

Deborah Grigsby is a Colorado-based photographer who specializes in creative editorial, wedding, and portrait imaging. Her idea of photography is unconventional and far from the ordinary – merging traditional photojournalism with off-the-cuff angles and edgy, digital artistry. Deborah’s relaxed and unobtrusive approach enables her to capture the subject as they experience the moment.

Deborah’s international projects include work in Kuwait, Qatar, Korea, Jordan, Iraq, Bosnia, Wake Island, Sweden, France, Germany, Italy, Slovenia, and the United Kingdom.

Retired from the Air National Guard after more than 20 years of service, Grigsby Smith, now a Department of the Army civilian, serves as the Joint Chief of Public Affairs Plans for Joint Force Headquarters-Colorado National Guard.

From: www.deborahgrigsby.com and Joint Force Headquarters-Colorado National Guard

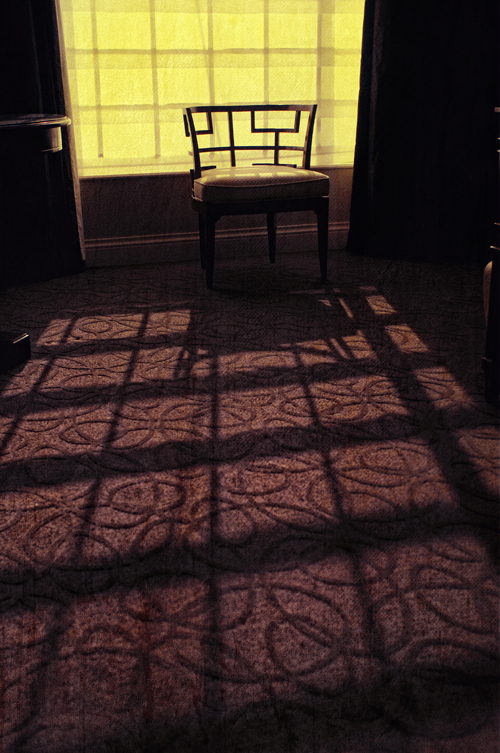

GRIGSBY_ChairAndSunlight: An empty chair in a Las Vegas hotel room tells an incredible story for me. The yellow glow from the window and the long shadows on the detailed carpet seem to simply replicate an artificial sense of reality as it struggles to conceal a sense of loneliness.

Deborah Grigsby: “As I struggled through the daily dance of deadlines as a military print journalist in Iraq, I began to see the correlation between my fledgling imagery and my words—how they could complement, as well as destroy, each other. I could see how a poorly chosen image could easily weaken an otherwise strong story, as well as how some extraordinary images needed few words at all—a stand-alone photo.”

“As we drove though the narrow, rutted streets of the tiny Iraqi village, children would gather in the streets to marvel at the soldiers as they worked. Often they would run along the side of a moving Humvee, gesturing for candy or cans of cold soda. On one particular street, a young boy followed our vehicle, smiling and waving at my hand-held video camera.”

“I channel the dark feelings I had as an “ugly duckling” teenager and use them to help others realize the key to a great portrait is not so much what the stylist picks out, but more so the emotions they project from within.”

“I find it kind of ironic that history has shown us that among the first casualties of war are almost always a culture’s artistic endeavors. Why is that?”

GRIGSBY_BlackLight: This piece is entitled “Nice Pear” and was part of an experiment I did a few years ago with blacklight photography. This body of work was awarded a fellowship from the Arts Alliance of Littleton. I was intrigued by the many facets of the subject, her skin and the pear that became noticeable under blacklight.

What do you like best about photography?

I think what draws me most to photography is its sheer candor and immediacy. The ability to capture as moment—and all its elements—as it unfolds, to me, is powerful. To capture a moment—a mother’s grief at the loss of her child, the last glint of sunlight before a storm, the precise movements of a ballet dancer on stage, the variety of expressions among people in a crowd, the beauty of sunlight on the human form—and hold it forever in a tangible form, is an intoxicating experience.

Whether the shot was carefully crafted by stylists in a studio or shot in a true journalistic form, it (photography) seizes a moment in time—a moment in time that will never again exist.

Photographers such as Annie Leibovitz, W. Eugene Smith, as well as WeeGee, Yervant, Peter Eastway, and Denver’s own Harry Rhodes have all influenced my eye as well as my work.

GRIGSBY_Aspens: Looking up at sun and color. This was shot as I was laying on the ground in an old cemetery in Central City, Colo. The light seemed to dance through the trees and the rustling of the leaves seemed to lull me into this shot.

What do you think of just before you open the shutter?

Primordially, I think about composition, exposure, and shape. In a digital world, it’s easy to simply shoot hundreds of shots without purpose or direction, so I have made a conscious effort to slow myself down; to meditate on the image I’m about to create—quality over quantity. I’ve finally been able to give myself permission to shoot with purpose. Pre-visualization is an important part of my work. Even if just for a fleeting moment, I try to pre-visualize the shot in my head before I open the shutter. It seems to help me have more control of the moment I’m trying to capture.

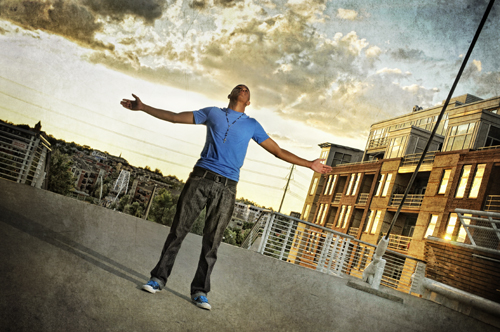

GRIGSBY_TheRelease: I love this shot for the many subtle messages it communicates. The young man seems to be crying out in pain, or is it joy? Perhaps he’s stretching his arms to the universe for guidance? The architecture, the light and the post-production grudge treatment amuse me.

Do you find yourself looking at the world and wondering how it would look as a photograph?

In some ways, yes. More so than looking at people or objects in the world, I tend to “see” light first, then the person or object. An open window, a shaft of light through a keyhole, a reflection in the deep black lacquer of a piano—these catch my attention far more than simply viewing the world as a whole. I find the light, and then try to place the subject in it. Sometimes, the light actually becomes the subject. Understanding how light behaves has helped me better understand my photography, as well as some of my digital post-production techniques.

GRIGSBY_BigSkyCowboy: This piece was recently on loan to the Colorado Gallery of the Arts and the Church Street Gallery as part of their annual Kaleidoscope Show where it took first place. The upward angle and exaggerated sky make this a personal favorite. It was shot as a winter snow storm was moving in from the west. I like the exaggerated effect of the lens, the distant stare of the subject and the detail in the sky.

Does your photography get along well with your writing in life, or are they “jealous” of each other?

As I struggled through the daily dance of deadlines as a military print journalist in Iraq, I began to see the correlation between my fledgling imagery and my words—how they could complement, as well as destroy, each other. I could see how a poorly chosen image could easily weaken an otherwise strong story, as well as how some extraordinary images needed few words at all—a stand-alone photo.

Words and imagery should never be “jealous” of each other. They are a delightful pairing, but yet equally powerful alone. Strong stories written with exceptionally vivid language may have no need for art or illustration, of any kind. The visual imagery created unfolds inside the mind of each reader, drawing on individual experiences and frame of reference to fill the visual requirement. In this case, an image may detract from the reader’s more “personal” experience.

On the other hand, a strong, carefully composed image may be so captivating it draws the viewer in, and simply through light and details, facial expression and shape, the photographer clearly communicates a desired message. Excessive verbiage may, in this case as well, influence the individual experience.

But much like food and wine, pairing words and imagery should never be left to guesswork. A good understanding of origin, style, technique, and shared “flavors” is essential.

GRIGSBY_DeadSeaJordanianSide: An interesting play of light and color on the Dead Sea, as seen from the Jordanian side. The setting sun filtered through clouds and dust are reflected in the salty sheen of the sea made these rich bands of color that begged me to shoot.

Does your Air Force experience share any commonalities with “illustrative photography?”

My experience in the Air Force served more as a launching pad for the work I want to create. It gave me the discipline, the basic skills, and the confidence to create bodies of work that served mission requirements. It also helped me “see” the coverage I produced in service to my country was not necessarily the work I wanted to produce for myself.

Pure photojournalism comes pretty much from the gut—and straight out of the camera. It is raw, unaltered and serves as a primary visual documentation of an event. “Fiddling” with images is taboo. So I spent many years as purist, believing that photo editing was a necessary evil, required only to rename files and embed data. But I felt my photos yearned for something more.

However, a 2006 lecture by Australian master photographer Peter Eastway introduced me to the concept of illustrative photography. His breathtaking, multi-layered masterpieces of composited images clearly smacked in the faces of photo purists—much to my delight. At that moment, I no longer felt “dirty” about manipulating images to create my own personal work. It was liberating and really was the door I needed open to find my voice.

GRIGSBY_AceLooksBack: This is a shot of retired Brig. Gen Steve Ritchie, the last and only U.S. Air Force ace since the Korean War. I was attracted to this shot, first by the light spilling over his shoulders. But I think what moves me most about this image is the fact he was lost in though–reflecting on his own accomplishments as they were read aloud as part of his introduction as a keynote speaker.

Despite all the horrors of armed conflict and battle you have witnessed, was war inspiring to you as a writer, journalist and photographer?

It’s true. I have seen many unpleasant things as a result of my wartime experience, and it always amazes me that people almost always assume the ugliness of conflict is a driving force in my work. Sure, it has affected my work, but more so it was the stories of everyday life in combat that had the biggest effect on my work. I suppose one could compare it to the works of American journalist and war correspondent, Ernie Pyle.

More so than conflict, it was the random acts of kindness between soldiers and locals, between soldiers from coalition countries, and among our own personnel that really inspired me to study the human condition through the lens. Graphic photos of the dead, spoils of war and gunfire surely garner attention, if only from a position of shock, but images and stories that whisk the reader outside the military mindset, and remind us of our humanity seem to influence me most.

I returned from Iraq a different person—a more mindful person. I came back a better person, a better writer, and a more thoughtful photographer, although it would be several years before I could ever feel comfortable with my voice as an image-maker.

Perhaps the most moving moment I experienced in Iraq came on a hot summer’s day in July of 2003. I had accompanied a team of explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) experts to the small village of Suq ash Shuyukh, south of An Nasiriyah. We were there to retrieve unexploded ordnance identified by the locals. I rode along to do photos and video. At that time, coalition forces often offered cash rewards to locals who would report ordnance of any type in an effort to stem resale and the manufacture of improvised explosive devices. Once disassembled and catalogued, explosive experts would then conduct a controlled detonation.

As we drove though the narrow, rutted streets of the tiny Iraqi village, children would gather in the streets to marvel at the soldiers as they worked. Often they would run along the side of a moving Humvee, gesturing for candy or cans of cold soda. On one particular street, a young boy followed our vehicle, smiling and waving at my hand-held video camera.

GRIGSBY_Dachau3: Inside the Jewish memorial at the notorious Dachau Concentration Camp in Dachau, Germany. What caught my eye here was the dreary weather, the structure and the female subject. As I sat on the floor of the building, the dense fog seemed to showcase the architecture of semi-open gate. The lone figure to camera right, facing the wall made me feel a sense of hopelessness.

He must have followed us for more than six blocks, never tiring. As the driver pulled over to wait for the last vehicle to join us, the young man rushed up to the window and with a huge smile on his face, he proclaimed in breathless, broken English, “I love you, Father Bush!”

Since that day, I have replayed that video segment over and over, both on camera and in my head, contemplating the motivation behind the young man’s proclamation. Was he truly grateful for the invasion of his country and the departure of Saddam Hussein? Was the statement simply a phrase he learned to charm soldiers out of candy bars? Perhaps was it something more sinister. I don’t know.

I look back now, more than seven years later, and with different eyes and a different heart, and realize the young man’s motivations were not important. What was important—for me—was the fact he was there on the street at the same time I was, he made an effort to follow his curiosity, and tried to communicate with us as best he could. Politics had nothing to do with the lesson I received that day. It was not about oil, it was not about governmental powers. It was about the most simple of human emotions—a greeting.

As a writer and photographer, I still embrace this young man’s tenacity, following my curiosity and taking risks to cross social and cultural boundaries in an effort to better understand the world in which I live—and simply just to say, “hello.” It’s about being there, following a story or idea, and then engaging the subject with whatever means you have.

GRIGSBY_TheCellist: A young cellist strikes a pose with her beloved cello in a local city park. I like the way the off-camera strobe hits the subject and how the cello appears to be part of her body.

Francisco de Goya’s paintings are famous for their disinclination to flatter, and their honest, unblinking style, which often caused discontent among his patrons. In this respect, can and should photography be a bridge between the two—the world as it is and the world as it can be?

Francisco de Goya’s paintings are indeed raw and unblinking. His ability to arrest conventional thought with imagery is to be admired. In his work, “Fatales consequencias de la sangrienta guerra en España con Buonaparte, Y otros caprichos enfáticos,” which I believe was originally entitled by de Goya as “Los Desastres de la Guerra” or “The Disasters of War” is a perfect example of how a series of images can not only tell a story, but attempt to influence public opinion.

I would like to see photography as a bridge between the world as it is, and as it could be, but such a bold wish is sure to stir discourse among purists, critics and other artists. I fear photographers and artists of all media and genre having to put a warning label on their work in an effort to provide some sort of legal disclosure the “imagery you are about to see may not be politically correct, nor conform to cultural, social, or economic norms.”

I find it kind of ironic that history has shown us that among the first casualties of war are almost always a culture’s artistic endeavors. Why is that?

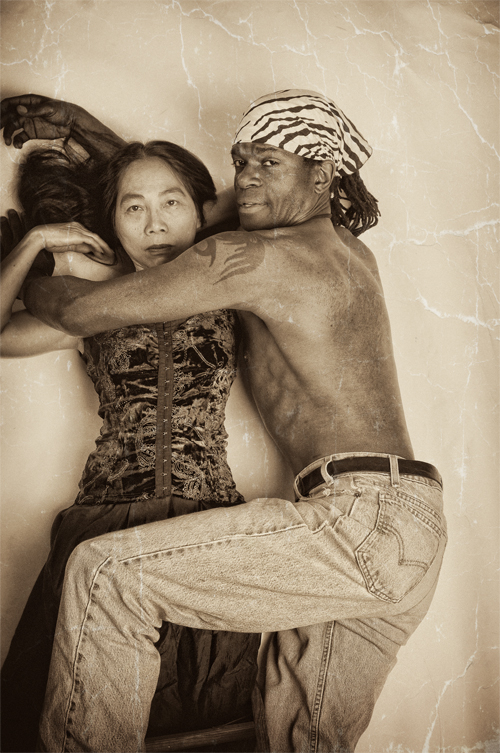

GRIGSBY_Interrupted: A thought, an action interrupted. Skin tones and body size, as well as facial expression give way to a suspended sense of privacy.

You want your subjects to “not only remember how they looked, but how they felt.” What about the photographer’s own emotions? Are they captured in the photograph, too?

I strive to create images that embrace more than just the elements of a snap shot. Yes, you were wearing a blue Armani suit with a red silk tie, but what your eyes really tell me is what I want to capture. I want my subjects, clients and patrons to look back on their images and be able to remember the experience and emotion of the moment with clarity. Over the years I have found that with most of my subjects, the best shots are those in which they are unaware of the camera. Even if just for a tenth of a second, there will always be a moment during a shoot in which the subject is truly at ease with their emotions and their appearance. I stay prepared for that moment.

Yes, many of my own emotions and insecurities are present in my photographs, particularly in my portrait work. As a child, I never had a photograph of myself in which I truly felt good about my appearance. One of my greatest joys is helping a portrait client overcome the demons of self-destructive behavior by creating a positive and enriching environment in which to shoot. I channel the dark feelings I had as an “ugly duckling” teenager and use them to help others realize the key to a great portrait is not so much what the stylist picks out, but more so the emotions they project from within.

In my personal work, I tend to use my heart—as well as my eyes—as a guide. Environmental elements in particular attract me—light, the smell of fresh cut hay, the feeling of loneliness that surrounds an empty chair in a Las Vegas hotel room.

Ansel Adams once said, “There are always two people in every picture: the photographer and the viewer.”

GRIGSBY_RebelRock: Members of the Irish folk band SixtySixDays toast themselves with a traditional shot of Irish whiskey shortly before a Denver, Colo. Performance. I like the way the spotlight falls on them in the darkened pub, as well as the crisp amber color of the whiskey and that fleeting moment in which they were engaged in themselves–unaware of my lens.

What do you think makes photography art?

For more than 150 years, photography’s stature as art has been questioned. Part art, part science… is it truly art or is it more of a craft? Does its ability to capture an image in seconds and produce an exact likeness in tangible form make it somewhat less of an art than oil painting on canvas? Is there more of the artist in a painting than in a photograph?

I find the ongoing spat between fine art painters and photographers somewhat annoying. I firmly believe the value of a photograph, as art, should be defined in the eye of the beholder. Art, to me, should be a visually appealing tangible element of work that creates an emotional connection between it and the viewer. That emotional bond can be as simple as a love of color and form, or a haunting message of the insolence of war. True, there are certain standards I think do help elevate a photograph from a mere snap shot to art—things such as composition, skill, exposure, printing technique and archival quality. However, there are also many cases where these elements may be manipulated to create an even more artistic form.

———————————————–

You can check out Deborah’s latest projects and shoots by visiting her website or Facebook page.

3 comments so far ↓

Nobody has commented yet. Be the first!

Comment