Christopher McCurry Interviews Sarah Freligh

Sarah Freligh at a book signing at AWP conference in Boston, 2013

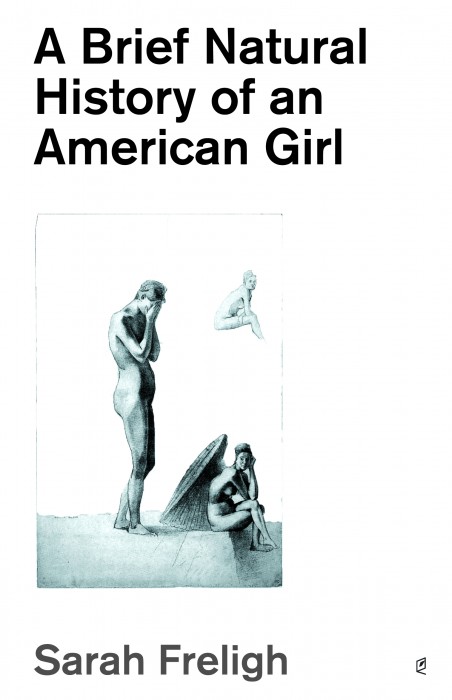

Tell us about yourself and your award winning chapbook A Brief Natural History of an American Girl (Accents Publishing 2012).

I live in Rochester, New York, on the North Coast of the United States with two cats the size of small dogs. And I thank you for that “award-winning” as a prefix to “chapbook.” It was years in the making, although most of the poems in there are still young and currently undergoing further revisions.

The title invites us to read the book as a guide to being an American Girl. In many ways, it is easy to see the common experiences, and yet reading the poems, the title doesn’t seem to fit perfectly, as if to suggest a kind of irony. Could you discuss the title in relation to the poems and speaker?

Irony, definitely. “American girl” is such a catch-all phrase, suggesting some kind of homogenized ideal as standard. It’s a term that’s very much of a throwback to the ‘50s and while I didn’t come of age during that time, I’m very much of that time, of its leftover mores and customs, and boatloads of “shoulds” and even more “should nots.” In many of the poems, the speaker is temporally distanced from “event,” in essence presenting a dual perspective that I hope allows for irony to mortar itself between the bricks of “real” and “perceived.”

A Brief Natural History of an American Girl (Accents Publishing 2012)

The book takes its title from the poem “A Brief Natural History of an Eight Grade Girl.” A poem that contrasts what can be learned about sex and reproduction from a textbook and what can be learned through day dreaming, fantasy, and experiences. Do think there are limits from what we can learn from “traditional education?”

As someone who is probably a “traditional” educator, most definitely. A student can read texts on writing ad infinitum—on rhetoric and theory and poets on writing poetry–but will that student be able to write a sonnet, for example? Likely not, though she may be able to expound at length on the history and tradition of the Italian vs. the English sonnet. You learn to write a sonnet by writing sonnets and even then, it’s new every time.

A writer needs to read, and readers need to write. “Practice makes perfect,” as I say in “A Brief Natural History of an Eighth Grade Girl.” The bugs obviously didn’t learn from textbooks.

The poem “Billy” appears to be the only poem that the reader could identify as male. Is there something in his experience as a valet driver “pretending the world was [his] kingdom” that is common to the American girl?

I would imagine it is to some “American girls,” but not to this one. I recently finished reading (for the second time) Patti Smith’s memoir Just Kids and I was struck by the “permission” she received not only from her mother and father, but from herself.

They encouraged her to be an artist, not by dragging her from lesson to lesson, but by giving her their approval. This permission enabled her to inhabit and eventually inherit her “kingdom” as a creative being. Do men maybe feel this entitlement from birth? Maybe. Certainly girls don’t.

Part of the history of every girl is the relationship between mother and daughter. Do you think there is something between the mother and daughter relationships in your book that make them “American?”

Hopefully, the mother/daughter thing is more universal than “American,” but there are many things in my book that are quintessentially of this place, if not time. Cars, certainly. There are a lot of cars in the book—driving around in cars, parking in cars, listening to the radio in cars, all that. And the car and the freedom it endowed in postwar America are certainly particular to place. The mother and daughter are like cars in many ways—they’re these self-contained vessels, sealed up and airtight. Each of them is driving alone at night.

How does a poem normally begin for you?

In a notebook, usually. I like those spiral Staples notebooks, the nine by six ones because I can slide them into my purse. I write down things I hear or see, sometimes riff off a line from a poem I’ve read. I do exercises that friends give me, paste pictures and newspaper stories in my notebook. Awful writing, all of it, and not very useful, that is, until the words have had time to sit and stew and percolate in their awfulness.

Once I’ve forgotten what I loved or what I hated, I go back and start yanking things out and typing them into the computer. Nothing ever springs forth fully formed.

Who or what inspires you to write?

Poetry does, certain poets or poems—too many to name here. Fiction writers, too. I’ll come home all fizzed up from a reading and start scribbling stuff. I think we have all this stuff inside us—not necessarily “memory” or “experience”—but things we’ve recorded and printed on our senses. We store them away and forget those things until someone or something unlocks them.

Are you currently working on any projects we can look forward to?

I’m currently working on a full-length collection that will contain most or all of the poems in my chapbook.

2 comments so far ↓

Nobody has commented yet. Be the first!

Comment