Peter Cowlam

Photo: MAMJODH

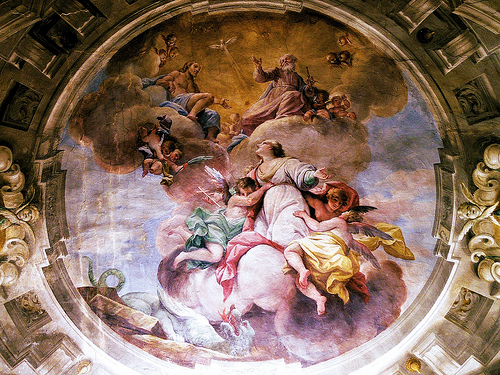

Borges – always a free thinker – at no time espoused Christian theology, but did regard one of Christianity’s foremost theological poets as having authored ‘the apex’ of all literature – namely Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), whose Commedia continues to be studied, and is regularly translated, by other writers. Dante composed his Commedia in three parts – Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso – in a verse form called terza rima (groups of three eleven-syllable lines whose rhyme scheme is aba bcb cdc etc.). The Inferno is a description of Hell, into whose successive circles various categories of sinners are consigned, and remain eternally. The Purgatorio deals with Christian Purgatory, which Dante conceives as a mountain of circular ledges, reserved for repentant sinners. Topping this mountain is the Earthly Paradise – the Paradiso – Dante’s vision of an aesthetically perfect world.

Dante casts himself as one of the characters of the Commedia, and selects as his guide through Hell and Purgatory Virgil, Roman poet of antiquity, and, significantly, pagan by a matter of only two or three generations (Virgil, 70–19 BC). Virgil’s Aeneid is the legendary account of the Trojan prince Aeneas, who after the fall of Troy laid the foundations of Roman power, whereas his Fourth Eclogue, in its celebration of the birth of a child to a Roman official, was believed in the Middle Ages to have been Messianic, a prediction of the coming of Christ.

Borges, in his essay on the Commedia, describes himself as a ‘hedonistic reader’, who never reads a book merely because it is ancient, but because of the aesthetic emotions it offers. ‘Aesthetics’ and ‘emotions’ for Borges belong to a very particular area of literary specialisms, and are not simply matters of imagery and musicality, of joy/sorrow, pain/pleasure, etc. Nowhere in Borges’s œuvre is it evident that the literary aesthetic is reductive to its corporal state, the body as the site of the senses and therefore prime in everything that is sensorily received or given. Similarly his sensibility, or his literary emotion, does not have much commerce in the quotidian exchanges of everyday human life.

What he responds to, and may even be slightly bewildered by, is an intellectualised emotion, which frames the notion of beginning (or I should say capital B Beginning) as an infinite regress, and Completion as a geometrical progression, to whose nth term can always be added 1, plus an ellipsis. In this sense he can be a lover of Dante, but unlike Dante can’t be a committed Christian, in whose Beginning is God, creator of heaven and earth (Genesis, 1:1), and whose End is the Resurrection (‘…Jesus shewed himself to his disciples, after that he was risen from the dead’ – John, 21:14) – or at least whose temporal end is the Resurrection, without which mortal redemption is not possible (and neither is heaven’s populace).

Borges pinpoints the Commedia’s aesthetic emotion in the relationship between Dante and Virgil, which he describes as ‘filial’ (Dante the son of Virgil). Virgil, because he’s a pagan, cannot accompany his charge beyond Purgatory, in fact is a sad figure forever condemned to that nobile castello, which is ‘filled with the absence of God’. Dante by contrast will see God. Dante will know, and understand the universe. Further than this, Borges isolates Canto XXVI of the Inferno as the Commedia’s high point, perhaps precisely because, for several reasons, it is representative of metaphysical being devoid of Christian hope. This is the episode of Ulysses, in a re-rendering of Homer’s Odysseus, who has been, in the pagan world, a traditional emblem of the soul’s journey, without a guide (without God as guide), to its celestial destination. The Greek word nostos describes that journey as circular, starting from and returning home, and between those two points encountering all of life’s adventures.

According to Homer, Odysseus completes his journey, returning not only to the bosom of his family but to the throne of his kingdom. According to Dante, Ulysses is punished for daring to seek out the mountain of Purgatory, at whose summit is the forbidden knowledge of the universe, a complete and ultimate meaning that it is not granted to mere mortals to know. This leads Borges to speculate that Dante in some way sees himself as Ulysses, a poet who has dared through his work to impinge on the mysterious laws of God. It is tempting to suggest that Borges is also Dante’s Ulysses, a triform who lives on that shifting dune whose origin is indeterminate and whose end is one of perpetual transmogrification. This is a condition that is sometimes called infernal.

6 comments so far ↓

Nobody has commented yet. Be the first!

Comment