Bob Baker’s interview with Jeannine Hall Gailey

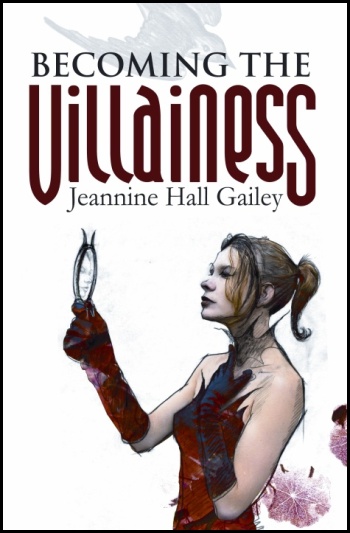

Jeannine Hall Gailey is the author of Becoming the Villainess. Poems from the book appeared on Verse Daily and on The Writer’s Almanac, and two were chosen for the 2007 The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror. She teaches at National University and volunteers at Crab Creek Review.

Suppose you are on a plane and the stranger next to you says. “What do you do?” What is your answer? Tell us how you feel about saying poet if that is what you say and tell us why you don’t say poet if you don’t.

I tell them “I’m a writer,” and if they ask “what kind,” I usually include poetry in the mix. I feel that probably accurately represents what I do, since, besides poetry, I also write reviews and essays and the occasional magazine article…and after all I did write a book on web technology some years ago. “Poet” sounds a little more rarified to me than “writer.” I’m not ashamed of being a poet, but most people just don’t have a context for “poet.” They either think of beatniks or people in Edwardian collars and sleeves.

What is your earliest recollection of poetry being especially meaningful to you?

I remember memorizing poetry at ten – E. E. Cummings’ “Anyone Lives in a Pretty How Town” and Louis Simpson’s “My Father in the Night Commanding No.” I also loved T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” which still makes me laugh, since I’m not sure exactly how empathetic a ten-year-old girl can be about a man’s fear of women and aging? On the other hand, Eliot was only in his mid-twenties when he wrote it, so maybe he didn’t know that much about aging either, at that point? My mother lent me her college textbooks of poetry, and I just fell in love. The one I am most fond of is the 1969 version of X.J. Kennedy’s Introduction to Poetry. My husband had it re-bound as a Christmas present to me recently, because it was falling apart. It still has my mother’s handwritten notes in it.

I understand your father was a robotics engineer. Was your household dominated by science or did literature play a part?

I definitely had more computers – and robots – around than the average kid growing up. My father would take me into the robotics labs, which had these huge robot arms, which I found fascinating. I learned to program at six on one of his TRS-80 computers, and I ended up getting my first degree in science, in biology. But my mom was a big reader, and that was encouraged in the house, as well. It wasn’t an “either/or” proposition – I was expected to excel at both science and literature, I think. In the manuscript I’m writing right now, I’m attempting to connect poetry and science.

What did publication of your first full length book, Becoming The Villainess mean to you personally and then to jump a bit of ground what does the title mean poetically?

Well, of course it was incredibly exciting to get the call about the book, the experience of working with Tom Hunley at Steel Toe Books was wonderful, and I really enjoyed collaborating with artist Michaela Eaves on the cover art as well. It was a thrill to see the book and hold it for the first time. But the thing that has meant the most to me about that book was going into classrooms and talking to high school and college students about the poems, about their reactions to them. I’m always honored when I get an e-mail and someone says: I related to this poem, or this poem moved me or helped me in some way. Because once something is published and out in the world, it can actually work. Once it’s removed from me, the writing can do what it was supposed to do.

“Becoming the Villainess” became the title late in the life of the manuscript, almost right before it was published. It’s really about the journey of the characters in the book from victim to villainess – really, traditionally, the only roles women have been allowed to play in fairy tales, in popular culture, etc. What are the choices women have had and how are they different now? If a woman takes power, does that automatically make her a bad person? Look at how the media portrays real-life women with power. Is there a choice for women outside of the victim/villainess paradox? How does a woman become a heroine, use her power for good? The book was meant to hold up a mirror to our perceptions of what women could become.

Your book is persona poetry running the gamut of characters from Ophelia and Persephone to Amazon Woman on the Moon with many many more between and around. What does persona poetry do for the poet?

I’ve always maintained that persona poetry is a useful counterpoint to the many years of self-reflective confessional work that has been dominant since the sixties. I love Sylvia Plath as much as the next person, and I like quite a few poets these days who work mostly in an autobiographical mode, but I prefer to get out of my own head.

What does it allow the reader that other forms do not?

It allows poets to use their imaginations, connect with larger worlds. I think that persona poetry allows people to empathize in a way that strictly autobiographical poetry does not, at its best. And it does something societally subversive, as well – if you re-write a popular narrative from a minor character’s point of view, in some ways, you take control of the story.

I think it gives us, on some level, a little bit more surprise – the reader doesn’t quite know what to expect if the speaker is Superman, or Orpheus, and it gets readers out of the somewhat tiresome trap of biographical readings: “Did this or that really happen to you?”

One unexpected truth, for me, about writing persona, is that it does become unexpectedly personal at the oddest time. In the middle of a poem about supervillains, or film noir vixens, I’ll find myself writing something very revealing.

In spite of your great success as a persona poet you have described yourself as a very traditional contemporary poet. What does that mean?

I just mean that, so far, I have stuck to fairly traditional forms – I mean, besides the occasional prose poem… I don’t write manuscripts using only one vowel, or a book of one-word poems, and my poems generally tell a story of some kind. I think that, especially with my first book, I wanted to write poetry that anyone could appreciate and embrace, even people without a special background in poetry or literature.

In some ways, I was writing the book for my little brother – maybe a nineteen-year-old version of him, anyway – an intelligent guy who reads avidly, but is more likely to know the latest video game trends than the latest Pushcart winners. In my newer manuscripts, I’m being a bit more adventurous in style, a bit more experimental or at least embracing some new forms – so we’ll see how it goes. I hope people are open to the new stuff.

What are your new publishing projects? Are we going to see more persona or something else?

I’m working on a couple of projects, actually, and they all involve persona to some extent. One is a series of poems examining some Japanese myths as well as female identity in anime. There are some really wonderful archetypes in Japanese mythology you just don’t see in Western folk tales – avenging/rescuing sisters is a common trope, as are disappearing/transforming wives. Anime – especially the work of Hayao Miyazaki – often features strong, complicated heroines.

The second is a series of poems on women who are “stuck” or imprisoned in fairy tales – Snow White, Rapunzel, Sleeping Beauty – and the ways that we can become stuck or imprisoned in our bodies. The latest is the most personal – an exploration of the Oak Ridge National Labs and a persona called “The Robot Scientist’s Daughter” – basically a fictional character that allows me to look at the work done on the nuclear bomb, and the resulting fallout, both human and environmental, in the area.

One reviewer of Becoming The Villainess said you could be the Billy Collins of poetry-reading teenage girls. What do you make of that suggestion?

Ha! That’s a funny thing. I hope that reviewer meant I was going to sell a whole lot of copies, and become a wealthy Poet Laureate?

You are a busy Professor in the Master of Creative Writing program at National University, how would you rate your job satisfaction?

I only teach part time right now, and do freelance writing and editing as well. I love teaching, I love talking about poetry with people who are also interested in poetry. It’s fun to introduce people to new writers, to new ideas. So I’m drunk with power! Just kidding.

What role does literary theory play in your creative process? Do we all need to read Derrida and Foucault?

When I was studying for my MA at The University of Cincinnati, I was introduced to deconstruction and all that, and I found theory really fun. My MFA program at Pacific University wasn’t very theory-focused, on the other hand; it was more focused on the craft of writing. I use literary theory more in my work as a book reviewer than as a poet; I think too much theory can wreck the work, you know? You have to keep two brains: a critical brain and a creative brain.

I think poets should read some theory, at least for fun, once in a while. I love reading intelligent criticism almost as much as I love reading good poetry.

How should American poets bring poetry to a wider audience and still maintain engaging complexity?

That’s a tough question. I definitely don’t believe in “dumbing things down” for a wider public; I think the wider public is plenty smart, and people don’t need to be talked down to. Unfortunately, I think poetry has got an undeserved bad rap as something boring, out-of-date – and I think the more we get good, relevant contemporary poetry in front of high school and college students, the more they’ll be hooked on it later in life. Poetry is work – that’s part of the fun of It. I also think the internet will be part of the solution to getting a wider variety of poetry in front of a wider audience. As independent bookstores and independent publishers have disappeared, it’s getting harder for the “average” person to find even one literary magazine within a twenty-mile driving distance, or books of poetry beyond Walt Whitman-Emily Dickinson-Billy Collins-Mary Oliver. But the internet is available in the smallest town, and there are a ton of great resources for people looking to read more poetry.

What effect does, or should, poetry have on the world beyond the page?

My hope is that poetry would make people reach for their better selves, gain empathy for others, cause people to linger a little bit and look into their – if it doesn’t sound too hokey – souls. But it doesn’t have to be uplifting – it can be horrifying – or terrifying or evoke anger or sadness. Or make us laugh.

One of my favorite poems in Becoming The Villainess is fairly short and titled “In the Faces of Litchtenstein’s Women.” Can we hear you reading this online anywhere and would tell us some about it?

This was inspired by a terrific Lichtenstein exhibit – I think it was in Seattle. I’m a big “pop art” fan, and Lichtenstein’s pieces especially. His genius is getting you to focus your eye on something you might just glance over – a bit of comic strip, for instance – and really heightens the glamour and intensity of it. Those yellows and reds seem so violent, so beautiful. All those crying women – and of course, Wonder Woman. I’ll put up an mp3 of a recording of “In the Faces of Lichtenstein’s Women” on my web site, www.webbish6.com, just for this interview!

Where can we find your work? Are you doing any readings soon?

Let’s see, I’ve got poems in the current issues of The Cincinnati Review, The LA Review, and Prick of the Spindle and poems upcoming in The Hollins Critic, Prairie Schooner, MARGIE, Court Green, Goblin Fruit, and qarrtsiluni.

I just moved to northern California, so I’m looking for reading opportunities in San Francisco and the North Bay!

2 comments so far ↓

Nobody has commented yet. Be the first!

Comment