Roland Boer

Photo: edhelien

Sterile white body suits, swimming goggles, face-masks, heavy boots and rubber gloves – six figures dressed as though they were entering a space craft or perhaps a laboratory with a highly contagious disease. Any plane from Australia, a swine flu hotspot (it was 2009), was always going to be suspect. They came on board after we had landed in Shanghai, passing through the plane in pairs. One zapped my forehead and, since doubt persisted, the other gently placed a thermometer in my mouth. I was cleared. But not so a grey-haired woman on the other side of the plane from where I was sitting; she gave a high reading.

Immediately the white-suited disease troops sprang into action. Two rows on all sides of her were handed face masks (three rows in Hong Kong). We had to wait half an hour for an official to come along; forms were filled out and signed and the infected party was marched off for quarantine.

One of them said, ‘I bet we’re not staying where we thought we would tonight’.

Another replied, ‘Yeah, I hope they have plenty of grog where we’re going’.

The woman next to me said, ‘Why didn’t she take a panadol half an hour before landing?’

Welcome to China!

Bicycles

I had wanted to come to China, the real China, for a long time. With more and more translations of my writings and talks of lecture tours the time was overdue. And I had arrived in the port city of Shanghai. I wasn’t overwhelmed by the size of the port (it has the highest volume of goods traded of any port in the world), nor was I overwhelmed by the haze or the size of the city (with a population almost equal to Australia’s 21 million). What blew me away were the bicycles.

Any city without masses of bicycles is a sad, sad place – like most cities in Australia. On this criterion, Shanghai is overflowing with joy. The wide bicycle lanes on all streets cannot hold the sheer number of bikes and motor scooters. They flow out into the main roadway, in amongst the endless trucks and taxis, up on footpaths, the wrong way on bike lanes – anywhere you can get a bicycle.

Some people haul mountainous loads – piles of fresh water, furniture, fridges, tools, building materials and whatever needs to be moved – on sturdy machines. In fact, tradesmen ride bicycles rather than utes (pick-up trucks). Others ride fold-up bicycles with miniature wheels. Some look like they were made before the Maoist Revolution. Others have obviously come off the factory line yesterday. Often there are two on a bicycle and no-one wears a helmet.

I was mesmerized by the intersections. Where traffic lights are present, cars and trucks stop (except for those turning left and the odd red-light runner). But not the bicycles, pedestrians or motor-scooters; they continue as if the red lights were in another universe. In their universe, the one of bicycles and people on foot, they carry on weaving in and out of one another, except that now the cars and trucks came at right angles to their own direction. It was as though those vehicles bearing down on them from right and left simply did not exist.

Photo: mckaysavage

I watched one man caught in a maelstrom of traffic, which collectively tried to deafen him with their horns. He was so indignant – swearing and gesturing – at the very presumption that cars should even think about cutting off his progress across the intersection.

I constantly expected to hear terrifying collisions, bodies spread-eagled across the road, and bicycles crushed under trucks. Somehow, against all the silly and pointless road rules with which I am familiar, the traffic manages. It is a mass of horns, swerving cars, tail-gating tucks, aggressive buses, foolhardy pedestrians, and cyclists in their own universe. Seat-belts are treated as amusing decorations and helmets are left to the timid. Yet somehow, some way, they all get to their destinations without mishap. Or I assume they do.

Close Encounters

Shanghai is a city full of people out running at 5.30 am. By 6.30 am the trucks travel in convoys through the streets. Not small delivery trucks, but semi-trailers full of building materials and soil from excavations. Building projects have, I was told, slowed down in the last few years, but everywhere I looked I saw cranes, bulldozers, backhoes, earth-movers, and of course the trucks. I heard the sounds of jackhammers, power-drills and saws. People are busting to get on with everything. It is a city full of energy.

I had not come to China merely to gape at intersection antics and marvel at the bicycles. I was here to talk to a press that is translating one of my books and a professor of biblical studies who showed me his bum crack. Having slept off the flight’s sleeping tablets, I was out early, dodging bicycles, motor scooters and trucks, to make my way to VI Horae Press on Jiangsu Road.

Lisa, or He Hua (prefixed by a ‘Ms’, as she told me clearly in an early email) was my main contact and we came to know each other quite well over the next couple of days. On greeting me for the first time in the flesh, she said she hadn’t recognized me at first. Obviously, I thought, since we’d never actually met, but the reason was not quite what I had imagined.

‘All the Australians I have met have red faces’, she said. ‘So I didn’t recognize you at first’. I imagined beefy, meat-eating Australians descending upon China, especially those who had spent too much time in the sun while working on their high blood pressure.

Lisa was from northern China, had studied English at university and had moved to Shanghai to work at the press. Lisa had no car, like most people, lived simply, and enjoyed life immensely.

‘Do you like poetry?’ She asked me.

‘I’m very choosy’, I replied, but we talked for ages about poetry.

‘I also love music’, she said.

‘Me too’, I said, ‘Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds …’

She gave me a skeptical look.

‘I bet you like classical music’, I said.

‘Oh yes’, she said. ‘And I love Shakespeare and Russian novels, especially Tolstoy’.

Photo: Luo Shaoyang

I could agree there, at least on the Russian novels. I mentioned China Miéville and Kim Stanley Robinson, who are not so Russian.

I was fascinated by the way she wrote in Chinese. The way the ideograms are constructed, much like a piece of furniture, can be an art. Lisa confessed to another love, calligraphy, and spoke endlessly about the great Chinese calligraphers. I thought about my spider-scrawl handwriting and kept asking her to write sentences and explain them to me.

But Lisa also became my translator at Horae Press, since Ni, the chief editor could understand English but not speak it so much. Better than my understanding of Chinese, I pointed out. I had dressed up mildly for the meeting with Ni, expecting a middle-aged man in a business suit and official manner who would ceremoniously hand me his business card. On this sweltering June day I wore long pants and a button-up shirt, and I was sweating freely by the time I arrived at the press.

I needn’t have bothered, for as soon as I met Ni I realized I was over-dressed. Dirty jeans, black T-shirt, greying goatee, ponytail and beaten up baseball cap. He stubbed out a cigarette into an over-flowing ashtray as I walked in. More of an aging rock-star than the CEO of an energetic and busy press.

‘We want to be the number one publisher of theological books in ten years’, he told me through Lisa.

Ni had initially allocated an hour and a half for my visit, but soon enough we hit it off. He took Lisa and me to lunch, with Lisa explaining all the terms for drinks and food and where they came from. I had opted for Rose-flower tea, whose name (which escapes me) alluded to the broken-hearted goddess who threw herself into a river when her lover disappeared. Very manly, I though to myself.

Photo: Chi King

We talked about theology, Germans, Ni’s experience with a large state publisher before he set up VI Horae, the multi-layered meaning of VI Horae (6 hours), the books on his desk, my other books, food, the state of biblical studies, China, lecture tours, Australia, travel, and Ni kept offering me smokes. Lisa was worn out by the end of it, but Ni wanted to meet again the following morning and talk some more. By the end of it I had agreed to become a consultant to the press on translations and to send him a pile of my own books as well.

As we parted, I observed that China may well lead the world in theology in a hundred years’ time. ‘No, thirty years’, said Ni.

‘Come back soon’, he said.

I promised I would.

The other person I met was the bum-crack professor. Liu Ping teaches Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) at Fudan University, a state institution, in the Department of Religious Studies. Liu lives with his wife and mother-in-law in a small, new minimalist apartment on the other side of Shanghai – in a city of 19 million that meant a one hour taxi ride belting along the new freeways. I did need to give the taxi driver a scrap of paper with the address in Chinese, a trick I soon learnt on arrival. Why not meet at the university?

Photo: rosemaniov

Liu had a bad back, he said, so much so that he couldn’t get out much. Brusque, tall and very evangelical (he wore a ‘Jesus’ T-shirt), Liu served me water freshened with herbs and Chinese peaches. We sat the by the fan on this sweltering afternoon and talked of peaches, Shanghai water, bad backs, acupuncture, hard beds, Chinese farmers, Bibles, translations (he thumped a pile of such works on the table), including one of my ‘complex’ and ‘surprising’ books, Marxist Criticism of the Bible, underground churches, seminaries (they are crap, he told me, compared to universities) and a teaching stint at Fudan as soon as possible for me.

Before I knew it a few hours had passed and we didn’t even have smokes and Chinese beer to help us on our way. Suddenly I was lined up against the wall with Liu for the photograph to commemorate this ‘historic occasion’ – Liu’s beautiful wife clicked away, continually telling us to smile (in Chinese, so Liu each time repeated the instruction). As for the bum crack, that turned on the stairs down to the roadway. Liu decided to walk me to the taxi and give instructions to the driver. But as we clumped down the stairs one after the other – he in his outside sandals, me in my joggers – he suddenly pulled down the back of his pants.

‘See’ he said, ‘my back. Can you see the marks from the acupuncture?’

All I noticed was his slightly wrinkled and hairless bum crack.

T99: Shanghai to Hong Kong

At last the time came for what I had really been waiting for: the train journey from Shanghai to Hong Kong (actually to Hung Hom station). Not the way people from overseas travel, I was told. Why don’t you catch a plane? Others opined. ‘It’s faster’. Not for me, an aviophobic who takes the strongest sleeping pills he can in order to bring on a coma for those dreadful long haul flights that are needed from time to time. No, I was after the train.

With a small slip of reddish paper that passed for a ticket in my hand, delivered by a sweating courier at the hotel moments before I had to go, I soaked in the hugely bustling Shanghai Central Station. Not before I had entrusted myself to a taxi driver who ran the gauntlet of Shanghai traffic with alarming adroitness and disregard for anyone or anything but our destination.

Baggage checks, locals with bags of food for the journey, and then we were led through to a spanking new train.

Carriage 10, room 1: the guard had three words of English, but they were enough. I laughed in pure delight when I entered the compartment – the size of a four-bed compartment but with two beds. The rest of the space had an easy chair, bathroom and large table. Was I to share it with someone, an attractive woman perhaps, a farting old man, a fat American? No, I was told, it was my own space for the next 24 hours!

Photo: Jakob Montrasio

I felt slightly guilty. This was a deluxe soft sleeper, usually reserved for government officials. Most of the train was soft or hard sleeper, four or eight beds to a compartment. The guilt lasted a few seconds, especially when the air-conditioning remained stuck on icy. A large thermos of boiling water came in, a tea cup, and we were away. I was mesmerized by the passage, sitting in the easy chair by the movie screen of a window, watching the land pass by.

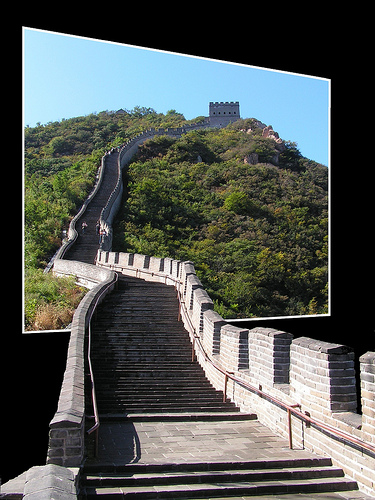

The new middle-rise apartment blocks on the outskirts of Shanghai gave way to construction lots with vast tents for the workers, muddy bicycles propped up against their sides. The ever-present trucks rumbled by on roads and dirt tracks. But I had seen all these in Shanghai and was after a different sense of China – at least as much as you can from a train window. The vertical, roughly cut mountains are such a contrast with the smooth, filed-down versions in Australia.

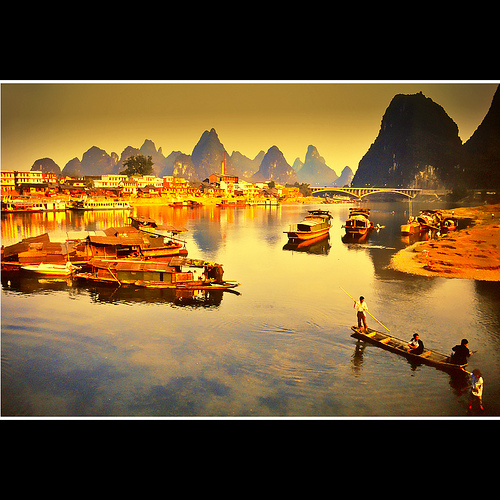

These jagged Chinese mountains seemed as though a giant child had been playing with clay, squeezing it through her fingers, letting odd-shaped pieces drop as she haphazardly moulded the other pieces into whatever shape she wanted. New mountains with vertical sides, all manner of strange outcrops, jagged edges and wafts of mist.

In between the farmers – evidently an inventive lot – laid out plots in the most unlikely corners: rice paddies, soy fields, and vegetables grew in the tiniest pockets or in terraces up the sides of the mountains, or occasionally in the flats where a river had carved out some space.

Photo: ZedZap(Nick)

And I was taken not merely by the pointy hats (isn’t everyone on their first visit to China?) but by the water buffalo. In Australia, up north in the tropics, water buffalo are mostly wild, shot for food at snooty restaurants and often regarded as destructive pests. Here a water buffalo would amble quietly on a rope behind a boy on the firm track between fields sunk in water. There one was at work in a field, up to its knees in water. And over there one quietly chewed while tethered to a post.

All along the route – almost 2000 km – came the villages. In the Australian countryside you can go for hours through bush, desert, or farmland without seeing another soul. Not in China, a country almost as vast but with more than 50 times the population of Australia. Every few kilometres another village turned up. Some were merely clusters of older dwellings, inventively proofed against rain and heat, but others were really double-villages.

The old buildings were still there, with an odd squatter or two, but nearby was a cluster of new buildings, small two or three-story apartments, often with a crane nearby finishing off the job. Yet inside, I was told, people kept to simple ways. No modern bathrooms, western-style lounge-rooms, or badly finished whizz-bang kitchens with buzzing appliances. Instead, you cooked in traditional style and still hung your arse over a plank in a common toilet and kept up the supply of fertilizer for the fields. An alternative life-styler’s paradise.

Photo: Jakob Montrasio

But there was far more to draw my gaze than outside the windows; the inside of trains is usually even more intriguing. As is my wont, I walked the length of the train. I passed by four-bed sleepers and the eight-bed hard sleepers, where people were making themselves at home, preparing to sleep with complete strangers and share each other’s space for the next day – a temporary village in motion.

In China, I was told, people feel comfortable with human breath; be alone too long and the spirits of the dead will join you all too soon. But that also means people find ways to use even the smallest spaces. In the corridors were small fold-out seats where two or three could leave the tight quarters and gather, chat and watch passers-by – like me, a lone, tall and fair stranger.

Eventually I found the dining car, where the kitchen was in full swing. Before I left, someone had warned me that food on the train was to be avoided at all costs. I braced myself for the worst, imagining the limp, soggy offerings from the buffet on the Sydney Melbourne XPT: pre-packaged micro-waved food that made airlines look like five-star restaurants.

Or perhaps a mythical dining car that was officially announced but simply couldn’t be found – as on the train from Belgrade to Sofia (Bulgaria). At least they had nicotine which you could scrape from the windows. On that journey to Bulgaria the single loaf of increasingly stale bread and a bottle of water went a long way in twelve hours. But I needn’t have worried on this train from Shanghai to Hong Kong.

There was freshly cooked food aplenty for next to nothing.

Half a dozen cooks were firing the stoves, peeling and chopping vegetables, lopping pieces off dead animals and tossing them into pots. Full of animated talk, jokes and teasing, they first loaded up scores of meal packages, which were then hauled through the train on a trolley to be sold for next to nothing. Only then was it time for the sit-down meal-goers.

This is where the finer issues of social interaction over food in China escaped me. In a place where people are perfectly comfortable insisting on attention, standing or calling out until it arrives, I had little to go on and no language to rely on. So I sat quietly and looked out the window until eventually an alert and very attractive older woman noticed me and made her way over. Silently she handed me a simple menu and I remembered the advice from Lisa:

Photo: Helga’s Lobster Stew

For food in Hongkong, you find the spirit of GuangDon Dishes (food in Hongkong is called so). The cooks try to maintain the original taste and colour, as well as making the food delicious. In other areas, cooks may try to give the food strong seasonings; this may be caused by geographical factors, such as in Si’Chun province, where the humidity is high and not good for bones, so people eat spicy food to keep dry. Also, in some northern parts of China, you find the food is more salty than in the south. This is because the North is very cold and food such as vegetables cannot be long-preserved, so people use less vegetables to make dishes. Finally they cook with more salt, and their taste becomes stronger … People in China tend to consider cooking as a form of art.

In this mobile kitchen simplicity and art go together. I am famished, so I order three dishes. Arranged in a semi-circle along with the bowl of rice, I dip into each one as I please. The nut and chicken dish – pieces at chop-stick size – in a delicious sauce takes a long time to eat, nut by nut, piece by piece. Each miniature mouthful washes over my mouth with taste. But the tofu is brilliant, fresh, just between firm and soft, soaked in a rich dark sauce along with a variety of field mushrooms that leaves

Australian dishes lagging at the back of the field. And then a simple collection of Chinese cabbage that makes the saliva shoot in my mouth. Can cabbage do that? Until now I hadn’t thought it possible. Either my expectations are so low that any reasonable food seems brilliant, or it was simply great, or rather simple and great.

Economic Paradox

By the last hour on a long distance train I look forward to end of the journey, like a small boy full of anticipation. Eagerly looking out the window, I enjoy the first signs of the city, the roll through outer stations, local trains, people waiting on stations and the ever denser buildings. Into the heart of the city, as trains do so well.

As we did so a paradox or two played with me. The Chinese government had recently announced USD $20 million for the study of Western Marxism. Back in Shanghai they had realised the potential for religion – inviting visiting scholars like me who had written a piece or two on Marxism and religion.

Chinese Christians might be a little evangelical, fundamentalist perhaps, but a buck is a buck and so they would do their best to get hold of some. That was only the beginning of paradox: here is a communist political system whipping the rest of world in generating capital. And they want to use that capital to encourage the study of Marxism! It reminds me of a story about Marx. His mother – frustrated that Karl hadn’t lived up to family and class expectations – once opined, ‘If only Karl knew how to make some capital instead of writing about it’. In a strange way, China seems to have realized her wish. After all, Marxists know capitalism better than anyone else.

3 comments so far ↓

Nobody has commented yet. Be the first!

Comment