Milena Kirova

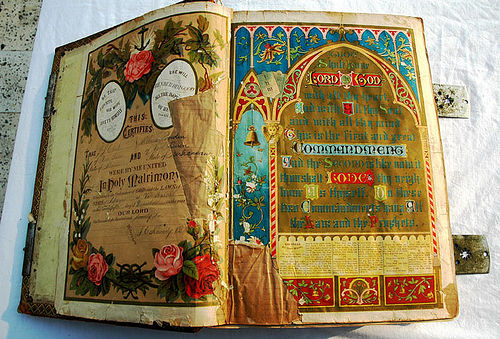

Photo: wonderlane

During the last three decades we have been witnessing an unprecedented rise of attention to the literary specifics of the biblical text. Teaching the Bible as literature has turned into a constant presence in the undergraduate and the postgraduate schedules of most universities in Western Europe and in the United States. Since the beginning of the 90’s it is also making its way throughout the universities of the so called “post-communist” countries.

As everywhere else, the secular method of teaching the Bible encounters a number of problems stemming from the domineering theological, mostly Christian, tradition of biblical studies. In spite of the great interest among students, there are still few university teachers who are skillful enough to venture an accomplished course. Under these circumstances even a complementary introduction of biblical knowledge inside a course of some other literary thematic (theoretical problems of literature or history of West-European literature for example) can mark a change and eventually – the beginning of a new academic tradition.

According to a popular belief, “among the various academic disciplines literary criticism would appear to have the greatest potential for shedding light on the task of biblical hermeneutics”. I should make explicit that this statement was written in 1987. Since then we witnessed the vigorous development of feminist biblical studies, which nowadays seem to be a significant rival of literary approach. These two trends share the ability to represent an accomplished alternative to the traditional biblical exegesis even within the secular paradigm.

A very important question then would be: how is this becoming possible? In an influential piece of reference literature, “The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible”, we can read that “literary critics in general do not believe it is necessary to use the traditional disciplines of biblical research or to employ the findings of these disciplines” . This is probably the start that answers our question by posing another one: what does a “disbelief in the traditional disciplines of biblical research” mean?

Ever since mid 19th century, the textual study of the Bible has been dominated by the so called historical-critical method. It was the German scholar Wellhausen who first introduced the idea that we should discern in the Old Testament five different sources, or five different types of textuality, created at different times between the 10th and the 2nd century BCE. The verbal corpus, as we know it, is not but the final compilation and redaction of very different pieces of writing that were brought together in order to constitute the canon of the Hebrew Bible.

Having in mind that the five main sources have progressively been fragmented to smaller pieces of authorship in a certain book, it is not difficult to imagine what the philological work on the Bible has been, after Wellhausen’s hypothesis was accepted as irrefutable truth. Generally speaking, it turned into an incessant work of distinguishing, defining and commenting on the historical circumstances, under which every single piece of discourse had been created by means of expert knowledge in ancient Hebrew and history of the ancient Near Eastern world.

Modern literary studies on the Bible appeared in the 70’s, bringing to the field of this five-source tradition the revolutionary idea that the Bible should be analysed and discussed as an entirety, a non-historical entirety, I should add. They introduced the synchronic methodology of approach versus the diachronic, or the historical-critical method of interpretation.

Some of them started even speaking of the necessity of “total interpretation”, having in mind a completely a-historical, if not anti-historical way of reading the Bible without paying any attention to the differences of vocabulary, style and narrative manner in the different parts of it. Even nowadays the opposition of synchronic v. diachronic makes the basic point of distinction between traditional and new critical approaches to the Bible.

Throughout the three decades that came after the beginning of the 70’s, the new literary approach to the Bible gradually spread among various schools and representatives of various methodological approaches inside Literary Studies themselves: New Criticism, structuralism, Reader Response criticism, deconstruction, Women’s and Gender Studies… Despite the obvious methodological differences which govern their work, they all focus on the biblical text as it is, without any care to its prehistory, biographical authorship, social and historical circumstances of writing.

The school of New-Critical approach was the first to dare enter the sacred field of traditional exegesis. In 1972 Robert Alter published a famous book, “The Art of Biblical Narrative”, followed by other American writers; British researchers, especially a group located at the University of Sheffield, in which David Gunn and Adele Berlin are just two names in point, joined efforts. As we know from their theory, the New-critics consider the literary work to be self sufficient, they regard it only as a piece of art, an arte fact, or a verbal icon. Consequently, the Bible represents for them a vast body of narrative techniques, poetic figures and rhetorical devices to be put to a most meticulous analysis.

The structuralist approach to the Bible as literature has been dependent mainly on the work of Propp and Greimas. Accordingly, it is the paradigmatic brand of theory (in opposition to Jacobson’s and Levy-Strauss’ syntagmatic approach) that dominates the field. Most work deploys the field of narratology; these are predominantly studies of plots and characters after patterns and theses, which are popular in structuralist linguistics and anthropology.

Deconstruction could have been a very appropriate methodology when applied to the textual reality of the Bible. The scholars writing along its theoretical guidelines have always been preoccupied with puns, implicit meanings and diversions of interpretation – all that, which has focused the centuries-long efforts of Talmudic rabbis. In a more daring turn of thought we can even call the rabbis precursors of deconstruction, being in a never-ending pursuit of hidden meanings. The main problem with modern deconstruction, very much unlike the ancient one, is the necessity of perfect skills in biblical Hebrew, and this refers not only to those writing on the Bible but also to those who are reading their work.

Let us now suppose that an item most generally called Literary Study of the Bible, finds its place on a post-graduate schedule. What are the directions, in which we could enunciate the thematics and the problematics of a perspective course? Understandably, it is not possible to discuss the vast array of all possibilities; I shall mention briefly just a number of them.

A study of genres would be a very popular solution. It has a long history since the late 19th century German scholar Hermann Gunkel introduced the commentary of literary genres into Old Testament and Oriental studies. Working basically on the Book of Genesis, Gunkel came to the conclusion that it represents a collection of legends, originally transmitted verbally, which have later been collected into cycles, and the cycles have been furnished with a framework and intrinsic connections.

An academic course, which seems appropriate for undergraduate students, could make good use of the Bible in order to illustrate the theoretical study of literary genres. Accomplished so far, the Bible itself can become a main object of interpretation at a postgraduate level of education, and the previously accumulated theoretical knowledge can be implemented to the task of defining and discussing the availability of certain genres. The possibilities in this line are almost limitless; there is – in a more or less accomplished state – a vast versatility of genres. Let me name just a few of them: the cultic hymn, the psalms, the didactic narrative, the prophetic story, there are parables and so on.

Problematics of narrative or narrative study is another solution of popularity. It might be centred on the biblical narrator who is a proverbially all-seeing, all-knowing figure and is supposed to have served as prototype of the “omnipotent narrator” for much of western novel. Narrative study may bring the research to non-traditional solutions of traditional enigmas in the biblical stories. A good example would make the popular story of Cain and Abel.

“The question over the rejection of Cain’s sacrifice has plagued readers of the Bible for centuries. Was Cain’s sacrifice unacceptable because it was not a bloody sacrifice? Or was it rejected because it was not offered in faith? The enigma of Cain’s sacrifice has arisen because the Old Testament remains silent on the subject of Cain’s motives for bringing his sacrifice and God’s motives for rejecting it. The text introduces Cain and Abel very abruptly and tells only briefly the story leading up to Abel’s murder.”

The New Critical researcher Bruce Waltke starts investigating the story in search of plausible motives for God’s and Cain’s behaviour by implementing techniques of narrative analysis. He makes use of Robert Alter’s assertion that character contrast is a much favoured device of Hebrew narrative. Waltke detects two differences concerning the ways in which the two brothers accomplish rite of sacrifice.

Abel brought to the altar the “firstborn” of his flock, and then offered to God the fat which was considered to be the best part of the animal. Cain’s gift is called just “fruits of the soil”, it is not specified as “the first fruits” and there is no allusion to its high quality. Waltke draws the conclusion that “Abel’s sacrifice is characterized as the best of its class and… Cain’s is not. The point seems to be that Abel’s sacrifice represents heartfelt worship; Cain’s represents unacceptable tokenism.”

The study of style is another way to bring the Bible into play when teaching literature because the ancient Hebrew library is a real treasury of rhetorical devices, both in poetry and prose. The narrative for example is highly dependent on the work of two basic mechanisms of literary character: redundancy and parallelism.

Since redundancy, and particularly – the amplification of certain events in different versions of one story, was very soon considered to be a result of the compilation work that brought together verbal pieces of different sources and the redactors didn’t dare leave over any of them. The three versions of the Creation story in Genesis make an example at hand. The opposite of redundancy, omission, or the elliptic mode of telling stories in general was also seen as a consequence of historical, rather than of narrative character.

The literary researchers of the Bible define both redundancy and omission as “typical features of Hebrew narrative style”. Instead of making attempts to reconcile the contradictions by a semantic or a historic interpretation, they investigate the very ways in which both redundancy and omission occur in the text. Omission especially has attracted a lot of attention being often labelled “gapping” or “narrative reticence”. The Israeli literary critic Meir Sternberg has called it a “system of gaps” thus asserting that there is a specific logic in what seems most illogical in the Hebrew text.

Parallelism is also qualified as a device of major importance, especially when the poetic books of the Old Testament – such as The Psalms, The Proverbs, The Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes or Job – are the main object of interpretation. Cases of parallelism may be traced either semantically or linguistically, depending on the methodological approach applied. The figure of chiasm has recently attracted a lot of attention by students of the Bible who follow poststructuralist or deconstructionist theory.

Though there is not time enough to expand in more directions of teaching the Bible as literature, I could not abstain from mentioning yet another one: biblical study in the field of intertextuality. All the books are composite texts in which different pieces of discourse interrelate with one another. The process of their redaction may be perceived as an ultimate exercise in the art of intertexuality. Michael Fox even states that it is the epitome of all Western intertexuality.

The books themselves incessantly refer to each other inside the frame of the whole canon. Let is think of the Book of Ruth for example; it is hardly comprehensible without knowledge in certain social traditions coming from other books of the Pentateuch, basically from Leviticus and Deuteronomy. Still another level of investigation is presupposed by the specific locations of the Bible among a vast body of texts – sacred and secular – which have been created in the Near East and Greece throughout tens of centuries. Recent discoveries of apocryphal gospels have brought this level of intertextuality to the front of biblical studies.

Apart from the possibility to teach the Bible as literature, I should also mention that biblical interpretation can be quite successfully integrated in many areas of interdisciplinary character, or where literature collaborates with other humanities. Let me just name a few of them: Studies of folklore and mythology, Anthropology, Psychology of literature, Women’s and Gender Studies, Nationalism and literature, Postcolonial Studies… The modern ways of teaching the Bible beyond the theological paradigm appear indeed limitless and nothing would justify the lack of them in the contemporary university curriculum.

We must admit though, that such a teaching also holds some risks, especially in countries with a rather strong religious tradition. It inevitably enters a contest not only with the existing theological literature, but also with the religious upbringing of these people, who regard secular comments on the sacred text as an offense and oppression upon their belief. The concept that the Bible is a sacred book, which cannot and must not be viewed as literature, is particularly popular.

A great author, such as T. S. Eliot, uncompromisingly wrote only 70 years ago: “The persons who enjoy these writings solely because of their literary merit are essentially parasites; and we know that parasites, when they become too numerous, are pests. I could easily fulminate for a whole hour against the men of letters who have gone into ecstasies over “the Bible as literature”.

Is the Bible literature? This question is only the beginning of a long and complicated debate. Let us put it aside for now and contend ourselves with the words of Northrop Frye: “The Bible is as literary as it can well be actually being literature”.

3 comments so far ↓

Nobody has commented yet. Be the first!

Comment