Jasmina Tacheva Talks with Film Critic, Cinephile, Film Blogger and Educator Girish Shambu

Girish Shambu is an associate professor of management at Canisius College in Buffalo, New York, and runs a community-oriented film-blog at girish. His writings have appeared in Framework, Cineaste, Artforum.com, and the collection Cinephilia in the Age of Digital Reproduction (Wallflower Press, 2009). He is Co-Editor of LOLA.

In one of your reminiscences about growing up in India you mention that throughout your childhood and adolescence you never had contact with horror movies. In yet another one, in regards to your first experiences in the USA, you say that on the first day of your arrival you literally spent hours in front of the TV, watching MTV – another facet of Western culture that you hadn’t been familiar with while living in India.

On the other hand, in your post “Hindi Popular Cinema” you talk about the fact that “many of the super-cinephiles and critics I respect most — like Jonathan Rosenbaum, Adrian Martin, James Quandt, Dave Kehr, Joe McElhaney, or Chris Fujiwara, to name just a few — share one thing in common: They’ve seen a vastly greater number of Hollywood films than they have films from that other large popular cinema in the world, that of India”.

Without any intentions of attempting to situate you in a national context, I’d like to ask you: What are some aspects of your life in India and the Indian culture that you deem unique and important to your formation as a cinephile and film critic?

I’ve been in love with movies since I was a child growing up in India. We think of Hollywood as being synonymous with movies, but in reality India has the world’s largest film industry. India makes about 1000 films a year in over a dozen languages. The country has a deeply movie-obsessed culture. So, all through my teens, I was a huge movie fan.

I would watch anything and everything that played at my tiny neighborhood theater: Hindi, Tamil and Bengali popular cinema; Clint Eastwood spaghetti Westerns from Italy; Charlie Chaplin comedies; Hong Kong action films; American political thrillers like The Parallax View and All The President’s Men; teen movies like the great and underappreciated Over The Edge (one of Matt Dillon’s early films), and so on. But at some point in my 20s, I became very serious about movies, something more than a “fan.”

I turned into a cinephile: someone who likes not only to watch films but also loves to think, read and write seriously about them. This is where film criticism comes in: it is a way of wrestling with our experience of a film — coming to grips with why we like or dislike a film or find it interesting — by writing about it. And in the process of writing about a film, discovering, in a deep way, both the film and our own experience and understanding of it.

Illustration by Girish Shambu

When talking about the difference between narrative cinema (“that which tells “stories”, however sketchy, and nods at some sort of dramatic closure, however open or provisional”) and avant-garde (“or so-called “poetic” or “experimental” or “non-narrative””) cinema, you write that ultimately “we impose upon a narrative film an obligation to somehow honor its story enough to give it some sense of a dramatic arc, some kind of resolution, some hint of motivation.”

In a later post you state the following: “Robert Bresson is my single favorite filmmaker but I’ve never been able to bring myself to write about his films… What I probably love best about Bresson is that for me, his films are projective surfaces. We don’t want a film to give us, all tied up with ribbons and bows, pre-digested and completely determined, an experience that does not include us or ask anything of us.

An artwork should provide a place for the viewer to project herself into it, constructing meaning in a process of collaboration with the artist. (E.H. Gombrich in Art and Illusion calls this the “beholder’s share” of the aesthetic experience.) Bresson creates this projective surface, for one, by means of an aesthetic of withholding. He creates absences which draw us into the work; we find ourselves filling these absences for ourselves by projection.”

So I started wondering: isn’t that perhaps exactly the foreseeableness of the narrative film, its expected self-driven logic, which hinders the full expression of its projective surfaces? Could it be inferred that avant-garde cinema allows for a greater “beholder’s share” precisely because oftentimes it provides more questions than ready answers?

When I was younger, my answer to this question was simple: Avant-garde cinema is “pure,” untainted, and vanguardist, while narrative cinema will always remain compromised, impure, and reactionary. How misguided, puritanical and blind I was! The situation is so much more subtle and complex. So, let me respond to this question in two parts.

First, a quick note on the difference between narrative and avant-garde films. Narrative films are, to one degree or another, commercial films; they tell stories, and they feature characters we can frequently ‘identify’ with. Even so-called “art films” that flout some of the conventions of mainstream cinema are still commercial to some extent, intended to circulate within market-sensitive networks of film festivals, art-house theaters, and the DVD distribution market.

Avant-garde films often set out to do something entirely different from commercial films: they try to create or produce new and unfamiliar experiences and sensations for the viewer. Rather than being about characters or plots, these movies can be about landscapes, or color, or light, or movement, or rhythm, or the human form, or all of the above. Further, avant-garde films often bring to the forefront the material aspects of the cinematic apparatus: e.g. the texture of the medium (Super-8, 16 mm, and video have such strong textural differences—something avant-garde films highlight rather than suppress).

If commercial films are like novels, avant-garde films can be likened to poems. They are usually made by just one person (the artist) and not a large cast and crew. They circulate in altogether different distribution and exhibition networks: small spaces like Hallwalls or Squeaky Wheel here in town; art galleries and museums; and experimental film festivals like Images, in Toronto, one of the largest such events in North America.

Very rarely, a canonical avant-garde filmmaker will briefly break through into the wider, more commercial distribution network – witness the wonderfully lavish Criterion DVD treatment given to films by Stan Brakhage or Hollis Frampton. We are fortunate to have this work preserved and available to the public in this fashion. But most avant-garde films don’t get this rare chance. Instead, they must be diligently sought out by the curious cinephile.

Avant-garde films often blaze the trail of stylistic innovation and experimentation – innovation that commercial films sometimes quietly absorb and assimilate a few years later. I have highly mixed feelings about this, but traces of the avant-garde movies of yesterday can too often be glimpsed in the TV commercials of today!

But avant-garde films, in my mind, are not superior to narrative cinema. The two kinds of cinema offer different registers of experience. Narrative cinema often deals with social and political realities and representations in a direct way that can engage large audiences – thus having the potential to cause that audience to reflect upon these realities of the world. This is not to say that avant-garde films are not, or can’t be, social or political or reflective – of course they can.

But the formal and stylistic ambition and daring of these films makes them difficult experiences for the all but the most adventurous and advanced viewers. This, I think, can limit their social and political value in the larger world. So, in sum, we need both kinds of cinema – and, importantly, we need a “leakage” of viewership and interest from one audience to the other.

I have many friends who watch mostly (or only) narrative films and other friends who do the same for avant-garde films. What film culture needs is a fluid movement between both – an exchange of learning from one field to the other. Each kind of cinema has something of interest, something innovative and inventive, to teach the other.

Illustration by Girish Shambu

In 2010, as part of the “Word and Image” series at Hendrix College in Arkansas, you gave a public lecture titled “Film Blogging, Cinephilia and Internet Film Culture.” Your favorite thing about blogging: “being able to educate oneself in public. Going through this process—trying to move forward, stumbling, groping, occasionally finding—in full view of the world does not always stroke one’s ego. Each week you find yourself writing not about what you know but about what you perhaps hope to learn from the process of watching, reading, and struggling to think through and articulate.”

Also: “More than anything else, the film-blogosphere, to me, is a learning community, a giant, dynamically changing group of film-lovers teaching and learning from each other, 24/7… In the pre-blog past, we had a relatively small number of specialist writers and a large number of readers. The blogosphere overturns this, permitting large numbers of passionate generalists to enter the cinema discourse in a serious and engaged fashion. Film-thought need not be left solely to specialists.

Cultural works like films ‘belong’ to the community at large and blogs allow that community, via a cost-unconstrained mechanism, to generate and disseminate discussion about cinema.” – we can clearly see how the empowerment of the audience has changed (= enriched) the dialogue of cinema, but what about the other part of this dialogue – the filmmakers – how has their role in it changed within the constant development of the means of communication, and are they making use of the advancement of communication technologies the way their audience is?

Compared to, say, 15 years ago, the contributions of filmmakers to film discourse has definitely increased. But there was always a rich tradition in 20th century film culture of the genre of the “filmmaker interview”. Magazines like Cahiers du Cinéma made it a point to feature interviews regularly, and since so many Cahiers critics like Godard, Truffaut, and Rohmer were aspiring filmmakers, they particularly enjoyed talking to their favorite directors at length about the nuts and bolts of filmmaking.

But since the advent of DVD and the Internet – and the ever-greater demands on filmmakers and performers to publicize, promote and “sell” their latest film to the public – we have seen an explosion of outlets and opportunities for filmmakers to communicate with the public. Also included here would be the plenitude of DVD commentary tracks, bonus featurettes, DVD interviews and press-book material which now accompany the release of films. There is an overwhelming amount of such “para-textual” material that is now available.

That said, I think there is a huge variability in terms of the usefulness of such material. It must be admitted: Not all filmmakers and performers are equally scintillating and penetratingly insightful. Far too many interviews and commentaries are, I’m afraid, not really worth the time. But for a cinephile who does a little bit of research, and cherry-picks the right material to spend time on, there is a bounty of good film insights waiting to be gleaned. A quick recommendation: there is a good series of filmmaker-interview books published by Faber & Faber in which the titles by Krzysztof Kieślowski, David Cronenberg and Paul Schrader are especially terrific.

Illustration by Girish Shambu

On account of Lukas Moodysson’s Fucking Åmål, a.k.a. Show Me Love, you write: “One has certain private traditions with ritualistic events like film festivals. At my first TIFF in ’99 I stumbled into an utterly winning teen movie (Lukas Moodysson’s Fucking Åmål…) and resolved to get a teen movie fix each year at TIFF”. Do you think that teen movies nowadays have finally taken their due place in the pantheon of cinema or are they still largely neglected and considered inferior to films for adults?

What, do you think, is or was the main reason for this undermining? – Is it perhaps the fact that they generally target a specific (thus, more or less limited) audience, or maybe because they are regarded more as pedagogical and didactic tools (or as the other extreme – as completely devoid of sense and purpose guff) than as expressions of art and conveyors of meaning?

There is an interesting and revealing situation at play here, especially in terms of taste. Teen films are “commercial” films that play at the megaplex and are produced by what Adorno called “the culture industry.” For this reason, they are often not taken terribly seriously by intellectuals in our culture. If they do become the object of serious study, it is in ways that merely reflect our culture, simplistically and symptomatically.

In fact, I would guess that many academics in the humanities would much rather watch a “Masterpiece Theatre”-style literary adaptation or a tastefully designed historical drama by Merchant-Ivory than they would Amy Heckerling’s films Fast Times at Ridgemont High or Clueless. And yet, both these films are, I would claim, among the highlights of American cinema of the last couple of decades.

They are highly inventive, nuanced aesthetic works – over and above their superficially (but not inaccurately) perceived status as “entertainments.” There is a wonderful recent book called “Teen Film: A Critical Introduction” by Australian scholar Catherine Driscoll that, I hope, will spur deeper interest and help change the state of affairs for this perpetually undervalued genre.

You remark that: “One of the niftiest things about the French New Wave was that most of its filmmakers — like Truffaut, Godard, Chabrol, Rohmer and Rivette — were cinephiles. They not only made movies, they watched them, wrote about them, passionately debated them, and held them close as they lived their daily lives.”

Can this be read in the opposite direction too, meaning that a cinephile, by devotedly conversing about films, could make a good filmmaker? Have you caught yourself, while watching a movie, thinking: “If I were directing, I would have done this differently”, etc.? Have you ever thought about making a movie, and assuming that all material conditions needed for this venture were at hand, what would it be about?

I think I would like to make an “essay film” – whose subject would be films, film criticism and film history. It would be about the encounter between films (clips from dozens of movies) and ideas (text written and spoken that would perform criticism). The wonderful French essay-filmmaker Chris Marker would probably be a guiding influence for me on such a project.

Illustration by Girish Shambu

In one of your posts you say that: “When I performed a quick informal statistical analysis on this recently, I found that over the last few years, a full third of the films I’ve seen are ones that I’ve seen before. In fact, the work of some directors all but demands repeat viewings (e.g., Resnais, Godard).”; in another one : “My DVD viewing of Le Samouraï last night (probably the fifth or sixth time I’ve seen it) had no such accompanying excitement. But the film remains eternally beautiful and hypnotic…”; in yet another one: “I returned to Lost Highway this week and found an entirely different film waiting to meet me (a different me to meet the waiting film). The structure now seemed purposeful and original—perhaps it took me Mulholland Drive to see that—and the deliberately abstract quality of the movie and its characters made the rejection of realism a virtue.”, and also: “these repeat visits are nevertheless valuable. They take us further, each time, into the work and its constituent details (its very ‘molecular structure’), allowing us a greater intimacy and thus fluency in thinking and talking about it.”

You also discuss the so-called Strombolian movies – a term coined by Nicole Brenez that you define as: “films that required considerable effort before you could understand and love them”. Each time when we go to a concert featuring the same playlist, our experience, due to the improvisations of the musicians or any other unforeseen circumstances, is at least slightly different than the last one; the same principle applies to theater performances – because they are performed live, there is always something unique and different each time a play is staged. Even writers have made an attempt to deliver to their readers a new experience with each re-reading of their books (e.g. Micheal Joyce’s exploration of the implementation of hypertext in literature in his book Of Two Minds, and the rise of fantasy roleplay gamebooks that lead to a different outcome each time they are played).

Movies on the other hand are more or less static in the sense that their content and the sequence of their plot remain constant each time they are viewed. And yet they succeed in rewarding their re-visitors with a new dimension of their beauty and meaning, just like the aforementioned forms of art. How do they manage to do that?

Very true: most people think of films as being static – but this is so only if we look at a film as being about nothing but story, incident, and narrative. In reality, though, a film is an astoundingly complex formal object: 24 images a second, hundreds of shots and cuts and compositions and movements, not to mention the documentary richness of each image (we must not forget that every film on some level is a documentary: of its settings, its actors, its decors, and so on).

What’s more, every new tool we bring to a film can completely transform the way we look at it. For example, knowledge of psychoanalysis can completely change our experience of a film like Hitchock’s Marnie or Lynch’s Blue Velvet. The longer I spend as a cinephile, the more I see films as dynamic, inexhaustible, and overwhelmingly “excessive” – in the best way!

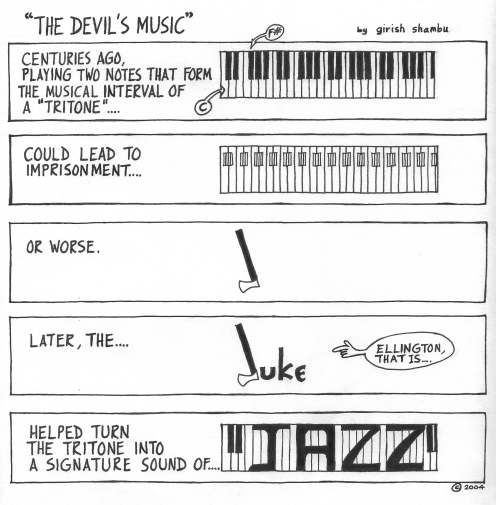

Illustration by Girish Shambu

In the vein of the last question, one can’t help but notice by the frequency of your posts about music that, as you yourself admit, “I spend more time listening to or playing music than I do watching movies”. This, together with the fact that you have written a paper on how to apply principles of jazz improvisation in the classroom and with your fervent amour for books, fine and applied arts, and so many other forms of art, leads me to believe that you deem art not as a categorized entity with different branches (one for cinema, one for music, etc.), but rather as a syncretic and indivisible ensemble of them all.

And also that perhaps this is precisely the reason why you value cinema so highly – as Vsevolod Pudovkin famously said: “Film is the greatest teacher, because it teaches not only through the brain, but through the whole body.” Can there be a greater emanation of the “syncretism” of art than cinema that employs all human senses at once?

You make fascinating points here, Jasmina! I’m going to turn the tables on you here and urge you to write a piece (small or big) about this – and please send it to me when you do! I’d love to read your thoughts about this. It’s a wonderfully fertile idea.

Could you tell us a little bit more about the idea behind the Internet film journal LOLA that you launched last August in collaboration with another film and arts critic, Dr. Adrian Martin? When can we expect the next issue?

Adrian and I want LOLA to be a journal where critics, scholars and filmmakers from around the world write about cinema – while also valuing literary style.

Adrian is from Australia, and I was born and raised in India. We have in common a certain distance from America (even though I’ve lived here for over 25 years). We are both bothered by the cultural isolationism of American film criticism and film studies – which is simply a manifestation of a larger isolationism that America has long been guilty of. Sure, American critics write about world cinema and film festivals, but in the U.S., because of our narrow linguistic competencies (which we are almost never embarrassed about), we are often oblivious about film theory and criticism being written in so many other parts of the world. It doesn’t register on our radar – in fact, for most of us, it simply doesn’t exist.

So, at LOLA, we’d like to remember that we are all part of a world film culture, rather than an American film culture. This will mean publishing writers from different countries, and getting involved in translating essays in theory and criticism from around the world.

Illustration by Girish Shambu

Links:

- Girish Shambu’s Blog

- Criticism and Context; Jia Zhangke by Girish Shambu on Public Republic

- LOLA

2 comments so far ↓

Nobody has commented yet. Be the first!

Comment