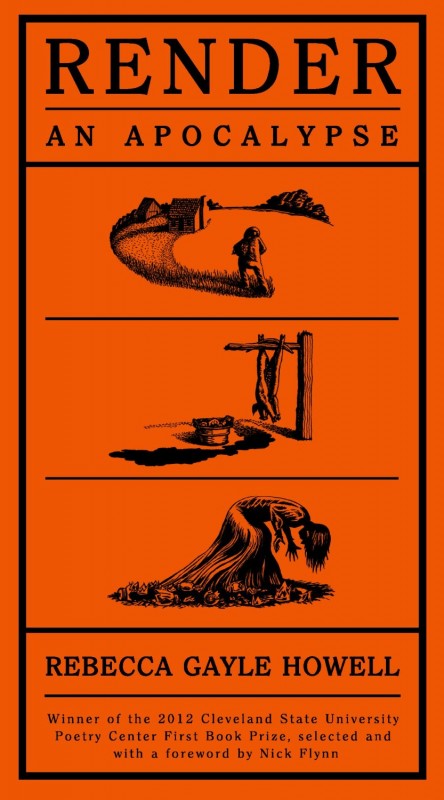

Christopher McCurry Interviews Rebecca Gayle Howell

Christopher McCurry:

Do you care to start at the very beginning? When and how you decided to write poems? How did Render: An Apocalypse happen?

Rebecca Gayle Howell:

My grandparents were subsistence farmers in Eastern Kentucky. They raised enough food to feed their family and that was it—my grandfather didn’t pursue the money economy. He never so much as logged his mountain. I admire their life choices more than I know how to say; when I remember love, I remember their land, its humidity, chickens, and hillside. But maybe this is the perspective of my privilege. My mother, who was raised as the daughter of subsistence, knew true poverty. What I mean is—she knew absence. And longing.

So my family’s narrative is dynamic. It shape-shifts, depending on who is telling the story. Throughout my life I tried to pin it down, until I realized I was mistaken to do so. My friend at the Fine Arts Work Center, Salvatore Scibona, told me the key was to take all of it, every last bit of the past, and throw it in the compost. What grows from compost is its own life. I suppose a point came when I realized we all share a shape-shifting narrative told by well meaning and unreliable narrators.

CM:

I want to talk at length about the narrative voice, and about your writing process as well, but for now, I am going to stick with the timeline, when, or maybe how, did you find the title?

RGH:

The title was actually the last to arrive. The word render means to take the unwanted parts of the animal and boil them down into something useful. But it also means to pay back what is owed. And, oddly, to invoke, as with metaphor or image. To bring into being. So, it was a word, a verb, that could meaningfully alert the reader to the book’s unfolding.

CM:

You describe Render as an apocalypse, yet there is an epigraph from Adrienne Rich: “Without tenderness, we are in hell.” I feel like tenderness is not a word most people would consider when thinking about boiling an animal’s offal, especially not when yoked to an apocalypse.

RGH:

Yes, well. Yes.

I’ve learned the hard way that, without tenderness, we are in hell. So Render begins there: a “you,” a man, a me, who has forgotten the ways of affection and who wakes up in a dark agrarian landscape. His survival depends upon his remembering what he’s forgotten.

To remember tenderness, to welcome it among our choices even when we think no one is watching and we are dealing with the least of these—a parcel of land, an animal’s offal, a war detainee—I don’t know, I think that process changes us, changes our sense of what is possible in decisive moments. Whenever I worry about where we are headed, my hope returns when I bear in mind our capacity for affection. In Render, the animals keep this secret.

CM:

Could you say more about the animals in Render?

RGH:

At the end of the poem “An Atlas For Return,” the cattle encircle the protagonist and lick him clean of his name. This act is consequential for the larger narrative of Render, but it’s not made up. Despite their intimidating size, cows are without prehensile appendages and so are left vulnerable to predators. When a cow is ready to calve, she leaves her herd and waits in solitude until she and her newborn are both ready to move again. The only protection she has is to lick the calf clean of its smell. So, the animals in Render remember. They clean the protagonist of his name, and with it, the smell of his bloodguilt.

CM:

Would you agree with me if I said you remind us of tenderness but you don’t let us be comforted by it? I’m thinking of the first poem “How to Wake” which ends “Watch yourself / You’ll get shit on // or kicked in the head”.

RGH:

That’s right. I wouldn’t read Render to feel comfortable. The reader is reminded of affection mostly by way of its absence.

CM:

Can we take a step back to the prologue poem, The Petition? There is a line, “Brother who is not the keeping brother, tiller / of earth…”, which I think embodies what you just said well.

RGH:

That line refers to the Cain and Abel story in the Book of Genesis, Chapter 4. Cain is made to work the land; Abel, to keep the flocks. When it comes time to present sacrifice, Abel’s gift is accepted, and Cain’s gift is not. He takes the news pretty hard, and two verses later Cain’s walking Abel into the fields to murder him. Thereafter, Cain is damned to homelessness.

So The Petition directly addresses the “you” of the book—it’s the only time this figure is name—and s/he is called “a tiller of earth,” and more specifically, one who is not his brother’s keeper. The warning of the original text, therefore, is implied.

CM:

Let’s talk about the narrative voice. Earlier you mentioned that all of our narratives “shape-shift with unreliable narrators,” and I heard you say at a reading that the speaker plays tricks. What role does this deception play in building Render’s landscape?

RGH:

Three forms of power exist in the book: the protagonist’s choices, the animals’ knowledge, and the narrator’s advice. Sometimes the narrator offers advice that will see the protagonist through, sometimes s/he offers advice that will require the “you” to learn the hard way. As you already noticed, a useful example of the narrator’s tricks can be found in the first poem of the first section, “How to Wake.” But that line becomes blurry as the book moves forward; it is to the reader to find her own ground.

CM:

How does the final poem, “A Calendar of Blazing Days” fit into this landscape? It seems markedly different from the rest of the poems, while remaining crucial to the narrative.

RGH:

The title refers to the final lines of the poem “How to Cure,” which ends the previous two sections. “Each blazing day counted / by every pound of flesh / you own.” This is, literally, how people projected the number of days it would take to smoke, or cure, meat. Of course, these lines point toward a spiritual reckoning, as well.

The Calendar‘s primary environment is the household of the same farm, and the “you” is in the one charged with the care of it. This is a role with a sweeping list of responsibilities, and for the first time, machines enter into the imagination of the book. Certainly, my grandmother felt it her whole life—a desire for something, anything to be simpler. She held, at once, an unflinching love for the land that nourished her and also real anger, since it was so much out of her control.

The Calendar, the whole book really, tries to hold in balance the unbearable choice between work and ease, trust and control. I think these questions are essential to us now; they are for me, anyway.

CM:

Stepping outside of Render, you are also a translator. Your work with Husam Qaisi on Hagar Before the Occupation, Hagar After the Occupation by Amal Al-Jubouri was a finalist for the Best Translated Book Award. What draws you to translating? How does it influence your own poetry?

RGH:

While brokering meaning between two languages that do not correspond, I learned that each word does, in fact, count. That accountability matters. Also, to translate a poem, I must become intimate with what is foreign. It challenges my assumptions about how to compose poetry, as well as my sense of boundaries and community.

CM:

You also use photo essays to document places, people, and issues important to you. What draws you to that form?

RGH:

Throughout my twenties and early thirties, I apprenticed under a southern writer and experimental art photographer named James Baker Hall. I worked in his darkroom loft, as well as in his writing studio, which is to say he and I spent a lot of time together at the crossroads of image and word. Jim was an ecstatic maker of images; influenced by his friends Ralph Eugene Meatyard and Minor White, his pictures are otherworldly, but also rooted in his own most personal story. I await the happy day when his work gains the notice it deserves.

My own pictures are plain jane; I want them to be. I want to bear witness. Dorothea Lange is important to me in this practice; she’d spend the whole day with her subjects, hold their children, become a friend. The resulting image was a collaboration between the photographer and her subject.

Anyway, I hadn’t thought of it before now, but I guess my writing is more influenced by my work with Jim’s photographs than my photographs are.

CM:

Who or what else drives your creative and documentary work?

RGH:

My gratitude and respect for my mother. She’s a painfully honest person; she tells me the truth as she sees it, even if it’s going to hurt.

CM:

Are you currently working on anything new that we can look forward to?

RGH:

After a bit of a dry spell, I’m back at my desk and writing. It’s too soon to talk about what’s happening there, so I’ll just say I’m very happy to be frustrated again. I’m reading the newly released James Agee / Walker Evans essay, and I’ve returned to Joel Meyerowitz’s Aftermath. I’ve also come back to Carolyn Forché; Blue Hour and The Angel of History. I don’t know how she doesn’t shatter, the way she opens herself to so much loss and love. That woman is made of Detroit steel.

O! And The Neighborhood by Tavares. Magic. Everyone should read it.

CM:

Thank you so much for your time, your poetry, and your careful attention to what makes us human.

Rebecca Gayle Howell‘s awards include a poetry fellowship from the Fine Arts Work Center and a Jules Chametzky Prize in Literary Translation. Library Journal chose Howell’s translation of Amal al-Jubouri’s Hagar Before the Occupation/Hagar After the Occupation (Alice James Books) as a 2011 best book of poetry. Hagar was also a finalist for the Best Translated Book Award (BTBA). Howell’s collection Render/ An Apocalypse was selected by Nick Flynn for the 2012 Cleveland State University Poetry Center’s First Book Prize. Her homeplace is Lexington, Kentucky.

2 comments so far ↓

Nobody has commented yet. Be the first!

Comment