Linda Cruise

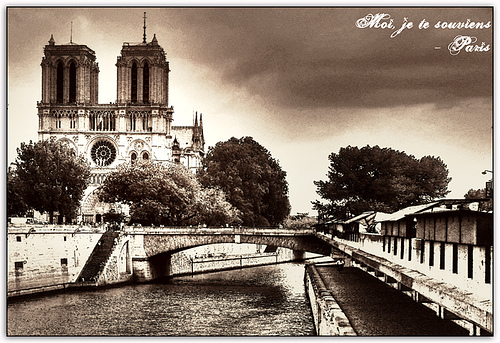

Photo: =ChevalieR=

Since the late 1940s, thousands of published books have been written on the subject of World War II—a seemingly infinite number of stories could be told about this one finite historical event.

Most of these works are nonfiction, but a significant body of that war’s literature exists in fiction form as well, including many classics (e.g., Wiesel’s Night, Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-five, Shaw’s The Young Lions, and Heller’s Catch-22) and some recent bestsellers (e.g., Faulks’s Charlotte Gray and McEwan’s Atonement).

However, of all the literature available, perhaps the most extraordinary example is Irène Némirovsky’s Suite Française, as it illuminates French Society during the early part of the war and occupation period, 1940-1942, in both its fiction and nonfiction portions; this includes a translation of the author’s original notes describing life in Occupied France, as well as her outlined plans for the novel’s five envisioned parts.

No other novel is known to have been written and published under such unique circumstances. This essay will take a closer look at these circumstances, retracing the conception, gestation, and miraculous—albeit “premature”—birth of Suite Française, in order to better grasp its literary impact.

To fully appreciate Suite Française for the remarkable fictional work that it is, one must first consider the historical context of Irène Némirovsky’s personal writing world—her individual perceptions as they related to the world at large.

No doubt these perceptions took shape within the context of living in war-torn Europe under Nazi Occupation as an exiled Jew, having been refused French citizenship. It is in this world—this context—that Némirovsky conceived her ambitious story idea for Suite Française and began its development.

No longer afforded her one-time socialite status as an accomplished novelist living in Paris, the Irène Némirovsky of the early 1940s became an embittered societal outcast, unwilling to give further allegiance to her adopted country or its people (Kaplan 1).

Included in the book’s supplemental material of Némirovsky’s diary notes, the author wrote of France’s betrayal of her: “My God! What is this country doing to me? Since it is rejecting me, let us consider it coldly, let us watch as it loses its honor and its life.” (Némirovsky 341) She had no delusions about her chances for survival either; just “[t]wo days before her arrest she wrote her publisher: ‘I have done a lot of writing. I suppose they will be posthumous works, but it helps pass the time.’” (Kaplan 2)

Despite the novel’s polished form and ability to stand on its own, the reader must be mindful that Suite Française—as it appears today in print—is an incomplete draft and not at all what Némirovsky envisioned for her final result. Unfortunately, Némirovsky had only enough time to write two of five intended parts before being arrested by the Nazis, in July of 1942, and sent to Auschwitz, where she died a month later from typhus (Kaplan 1).

In an online book review, Kaplan articulates, “Suite Française raises fascinating questions about what matters in the experience of reading: content or context. The context of Suite Française is endlessly fascinating—the recovered manuscript, the deported writer, the ambiguity of her choices and the cruelty of her fate. Then there is the novel itself.” (1)

What makes Suite Française rise above other WWII literature is that it was written during the war, giving the writing a powerful sense of immediacy and urgency that is simply not possible with hindsight. Urgency is created because while writing, Némirovsky’s perspective is limited to the “here and now.”

She did not have the obvious advantage, as later writers would, of knowing how the conflict was to be resolved. Would Germany be victorious or would Britain? Would the Allies be able to defeat the Germans and liberate France and the rest of Europe before it was too late for her Jewish race? Némirovsky died too soon to ever know; and so, in the same way Anne Frank lives on beyond her death through her diary’s story, Némirovsky lives on as well through Suite Française. Kaplan recommends such authenticity in the writing be read:

through the lens of Némirovsky’s found manuscript and the tragedy of the Holocaust. It’s impossible not to think of the miracle of Némirovsky’s surviving last words when you’re reading, and this context gives the book an importance, a shimmering sense of surplus value. (1)

Through her masterful storytelling, Némirovsky creates for posterity an eye-witness account of that period’s extreme living conditions—the humiliation felt by a conquered people, the disruption of daily life, the sacrifice required of them as the Germans imposed their communal mentality.

During the writing stage of Suite Française, Némirovsky noted in her diary the need for emphasizing the “struggle between personal destiny and collective destiny” (356). Elsewhere, she surmised the Nazis were “trying to make us believe we live in the age of the ‘community,’ when the individual must perish so that society may live, and we don’t want to see that it is society that is dying so the tyrants can live” (346). In no unspoken terms did she write about what it must have been like or what it might have been like during those extreme times; but rather, she wrote about what it was like—virtually as the story unfolded.

Fleeing Paris after France’s 1940 defeat forced Némirovsky’s family to take up residency in the small, Burgundian village of Issy-l’Evêque—though oddly still within France’s Occupied Zone. It is there the author launched her epic work, “writing…with a sense of urgent foreboding and nothing but her memory as a source,” as pointed out by the book’s English translator, Sandra Smith (ix).

Némirovsky envisioned the completed Suite Française to be a modern-day equivalent of War and Peace. Originally writing the story in her second language, French, the Ukrainian-born Némirovsky was able to broaden the novel’s literary scope by utilizing both the socio-cultural insight of a “native”—having lived in France for over twenty years—and the emotional distance of a “foreigner,” like no other WWII novel achieves.

Today, Suite Française can be hailed as the earliest work of fiction relating to the Second World War, thanks in large part to Némirovsky’s foresight, but no doubt to a bit of luck as well. Just before the author and her husband were arrested by the Nazis, Némirovsky’s daughters were hidden safely in the care of family friends, along with the Suite Française manuscript.

Even so, the manuscript did not come to light until recently when the eldest daughter finally read it and recognized its literary worth; it was published in English for the first time in 2005, more than 60 years after Némirovsky’s death.

Being a Jew in Europe during Hitler’s reign of anti-semitic terror was by no means easy for Némirovsky, but it did create the set of unique and challenging circumstances that gave birth to Suite Française. Such a monumental work as Suite Française exists in a rare class of fiction writing, as it has both literary and historical significance.

In the words of Myriam Anissimov, who wrote the French edition’s preface, “we are finally able to read the last work of a writer who had held a mirror up to France at its darkest hour” (395).

Works Cited

Kaplan, Alice. “Love in the Ruins.” The Nation 29 May 2006. Online posting. 11 May

2006. The Nation. 2007. 15 Jan. 2007 <http://www.thenation.com/doc/20060529>.

Némirovsky, Irène. Suite Française. New York: Knopf, 2006.

4 comments so far ↓

Nobody has commented yet. Be the first!

Comment