Jasmina Tacheva

Photo: Pioneer Library System

Tim O’Brien (born October 1, 1946 in Minnesota) is an American novelist who often writes about his experiences in the Vietnam War and the impact the war had on the American servicemen who fought there. His short fiction has appeared in The New Yorker, Esquire, Harper’s, The Atlantic, Playboy, and Ploughshares, and in several editions of The Best American Short Stories and The O. Henry Prize Stories.

In general, I like all kinds of movies with two big exceptions: comedies and war films. The former don’t appeal to me because they are too unrealistic and the latter – precisely because of their morbid realism. I guess this attitude has influenced my literary preferences as well, for I’ve noticed I tend to stay as far away as possible from two genres of literature for basically the same reasons: fantasy and war stories. I don’t seem to be able to force myself into reading a book that I know in advance has no tangency with the real world whatsoever.

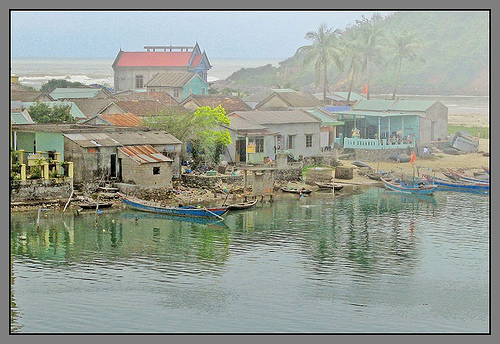

Photo: thinhgrapdes

Yes, it’s the ideas, the metaphors, the message behind the imaginary symbols and characters that count, I know, and yet… perhaps the fear of losing the gist of it all somewhere between the parallel paths of reality and mysticism that never ever cross, is what prevents me from embarking on this far too risky journey of translating magic into real-life ideas. However, for some bizarre reason, the other extreme – the too realistic war stories – stirs my mind with almost the same horror, if not even greater. But why? Isn’t their message directly stated on the pages of the book, staring at me with its perfectly sound clarity and all the hints that point at it like neon-signs, making it nearly impossible for me to ever lose the thread; then why does this kind of stories nevertheless scare me to the point of nervous shudder?!

It took me just one Tim O’Brien’s story to find out. And the line separating the world of fantasy from the realm of war experiences proved to be a narrow one for me. It really has to do with the impossibility of experiencing any of the two states – the state of magical surreality and the state of brutal war. This is my reasoning: Ok, no matter how hard I try, I will never be able to experience what it’s like to be a… six winged red dragon, spitting fire, say, or a platoon leader in Vietnam for that matter.

Either seems so far away from my way of living, that the mere attempt to imagine being any of them gives me nothing short of a headache. And how can I be able to fully grasp the meaning the author has invested in his or her work, given that I have no way of putting myself in the shoes of his or her characters? “The Things They Carried” showed me just how faulty these assumptions are. When I first opened the book, I was taken aback – not only did I realize it’s a hard-core war book, but what is worse – the reviews on the back cover shamelessly stated there was also something surrealistic about it, a great dose of “metafiction” – a dose that, I was sure, would prove deadly to me. I was wrong. What is more, I feel guilty.

No other piece of literature has ever made me feel guiltier than this little collection of stories. I guess the reason for that inexplicable guilt is that the book justified not only its own right of existence, but the meaning of all other works of art that tackle the subject of war. For it proved to me that although no one at my age who is not in the military, can fully imagine what it’s like to be a soldier in the Vietnamese wilderness, surrounded by enemies, uncertainty and the all-consuming fear of death, still there is a great point in reading these stories; a point that the realization of our bounded imagination cannot overshadow – the fact that they are so humane.

For me, a spoiled urban girl with no knowledge of the military whatsoever, it was hard to accept that something, involving such horrible bloodshed, death, terror, brutality and so many casualties, like war, can have a beautiful side to it, a humanistic one. And yet, this is exactly how Tim O’Brien won his way to my heart. His stories demonstrate that indeed, war can be picturesque and noble and tender and loving, because what is war but armies fighting against each other? And what are armies? Groups of people; people who in most cases, to be sure, are not the ones elicited the war; ordinary people like you and me, and people are picturesque and noble and tender and loving. O’Brien is not trying to convince his readers that war is good, not in the least, for besides its beautiful side he describes its atrocities and its unfairness and horror, but my feeling is that instead of overclouding its beauty, they enhance it.

Photo: Suriaa – I returned from China

That is because the author succeeds in showing that the ferociousness and savageness of killing people that we deem to be typical attributes of war, are actually not natural – they are enforced upon the soldiers by necessity – either kill or be killed. They don’t really have any other choice, and this is the ultimate justification of war’s beauty O’Brien has so exquisitely conveyed – the men, sent to Vietnam, have dreams, hopes, fears, strengths, weaknesses just like any other human being, and this is what makes these stories valuable to us today and will continue maintaining their worthiness for centuries to come – everybody can relate to their feelings; it doesn’t take a back-in-time journey to 1968 Vietnam to see what they are experiencing, because we are all humans and we all have our battles to fight, no matter if they are physical or psychological.

Much in the spirit of “How to Tell a True War Story” I’d like to share my genuine fascination by all the various possibilities of magnificent diversity Tim O’Brien illustrates through his stories:

A true war story can be an expression of transcendentalism. It can be the connection between the tangible and noetic aspects in life. In the story “The Things They Carried” this is depicted by the relationship between the physical and spiritual load of every character. Besides the ammunitions, weapons, sleeping bags, canned food and personal lucky charms like Dobbins’ girlfriend’s pantyhose, every man “carried ghosts”. The detailed description of each item’s exact weight and function is what separates the ordinary reader from the soldiers – a person like me will most probably never have to come near any of these military objects. But the intangible things they carry are what helps the reader relate to these men, for we all carry hopes and dreams and fears and disappointments.

The soldiers will sooner or later go back home – dead or alive, but the point is, one day all of them will dispose of their military tools and uniforms, they will become civilians like any other American, but the spiritual load is something nobody can easily get rid of. Moreover, unlike their corporeal belongings, their weight cannot be estimated. At least not in terms of pounds or grams: “Grief, terror, love, longing – these were intangibles, but the intangibles had their own mass and specific gravity, they had tangible weight.” Lieutenant Cross, for instance, measures his love for Martha in terms of human life – the dead of Ted Lavender is how much it really weighs. He attempts to get this weight off his mind, he burns her pictures and letters, and forbids himself to dream about her anymore, but he realizes that “you couldn’t burn the blame”.

Moreover, in the next chapter, “Love”, it becomes apparent that even after all those years, he still loves her dearly: “Maybe she’ll read it and come begging. There’s always hope, right?” Yes, all the heavy M-16s, the grenades and gun cleaning kits, are now left to rust and oblivion somewhere in the Vietnamese jungle or in some deserted military warehouse, abandoned and forgotten, but the emotional load still lingers around, lying heavy on the soul. This makes me think of my coming to the United States. In one way or another, it was just like taking off a military uniform and disposing of the ammunition of all the battles I had fought with my country, myself, my friends and foes.

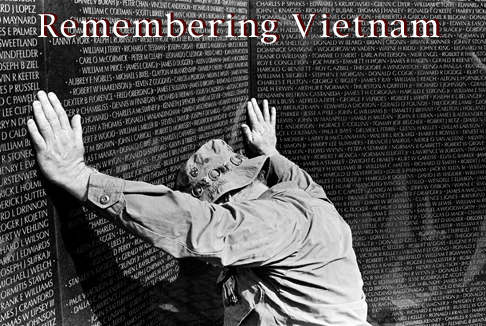

Photo: melaniedornier.photoshelter.com

To an extent, I thought I had moved to America ready to make a fresh start, as if nothing good or bad up to that point had really mattered. I was wrong. In a way, I have dragged my emotional intangibles all the way to Buffalo – the friendships, the memories, the experiences, my whole life – I couldn’t just erase it, it was there, inside of me, weighing on my mind, constantly reminding me of the past. I guess there is no way to escape from yourself, from your mistakes and successes. You can’t hide from the reflection in the mirror and you can’t forget who you are. But at the end of the day, I believe that the sooner we all accept this fate, the better we will live, because the reconcilement with our weaknesses is the first step we have to make in order to continue our way in life. Otherwise we just mark time in a vain attempt to change the unchangeable – to dispose of the undisposable load we carry.

A true war story can be a moral lesson. It can present ethical dilemmas: “I couldn’t make up my mind. I feared the war, yes, but I also feared exile. I was afraid of walking away from my own life, my friends and my family, my whole history, everything that mattered to me.” In the story “On the Rainy River” the narrator talks about the choice between going to Vietnam and immigrating to Canada to escape from the war. Contrary to common sense, the moral category of courage here is reversed: a courageous act according to the main character would be the venture of escaping, rather than following his bounden duty by enlisting. This paradox arises out of the stereotypical concept we have about war: going to war has become a paragon of courage – men and women risk their lives in the name of freedom/democracy/justice or any other fair cause.

In this train of thought, the meaning of the Vietnam War is even greater, because it serves the liberation of a nation other than the United States, which means that American soldiers are going to war jointly and gratuitously, without expecting anything in exchange. Can there really be anything more courageous than this? According to the narrator, the answer is yes. This has been puzzling me for quite a long time, and then it suddenly dawned on me – I remembered that I had experienced a similar moral split, that, although far less significant than this one, has caused me the same amount of excruciation the protagonist is faced with. When my friend died in that absurd car accident, I started asking “Why?”.

At first I blamed her death on bad luck or other sort of upset karma. Then gradually a network of people, events and circumstances started forming in my mind, and finally I realized that since the very first day of high school everyone in that school has been responsible by intentional and unintentional acts for the accident: the driver had been pulled over by the traffic police at least twice, but they didn’t even issue him a speed ticket, because he had bribed them; we all: students and teachers alike, knew that he was driving without having passed the driving test; even the principal was aware of this, and yet nobody said anything, because… nobody really cared and because before the car crash… I guess we all thought there wasn’t anything particularly wrong with it or anything – we didn’t deem it unusual or necessarily bad. Furthermore, the boy’s family was well off, he liked showing off and my naïve classmates, the teachers and the principal himself were constantly flattering him.

Photo: brookshiresean

He skipped school a lot but no teacher ever dared to mark his absence and they would let him cheat on exams, which made him appear like a perfect student. All this negligence ensured his clean slate at the trial; it served as extenuating circumstances, so he was sentenced to one year of probation. The last words my friend had heard were: “Let me show you who Mister Speed is!”, and they had come out of the mouth of this guy, who had caused her death in such a stupid and arrogant way, and his only punishment was a year of grounding?! What is worse, nobody in the whole school thought he was guilty. Nobody blamed him. On the contrary, they were trying to defend him, to convince me that it was her fault, because she had known he didn’t have his driver’s license yet. I started hating everyone, the whole school, I wanted them to pay for their stupidity and hypocrisy, I longed for revenge.

The most courageous alternative I could think of, the sole right thing to do, was to move to another school as soon as possible. And yet, I didn’t have the guts to do it. I stayed there and hated myself even more, because I realized what a coward I was. I preferred to stick with that “evil nest of vipers” as I saw it, so that I would be able to apply to a college in America without the difficulties that a possible transfer to another high school during my senior year could present. I chose to secure my future instead of vindicating my best friend’s memory, and I have been blaming myself for that horrible act of spinelessness ever since.

However, when I read “On the Rainy River”, something inside of me cracked and a most flippant thought crossed my mind: What if my very staying there was more courageous than a contingent transfer? For, after all, the endurance of meeting these repulsive people, of looking at myself in the mirror every single morning, of seeing her empty chair every day, isn’t that at least a little courageous? Doesn’t it require enormous inner strength, all this unbearable putting up with this tragedy?

In the end, the narrator ended up going to the war. He didn’t act on the opportunity to escape, and consequently – didn’t regard himself as being in the least courageous. I, however, believe that he has been brave enough. Because I know the cost of seeming dignity; of pretending that the disgraceful thoughts about and even an initial attempt of escaping have never existed in your mind. I have experienced this emotional burden as well, and now I am sure that it requires a great deal of courage to live with this stigma, far greater than an escape would require…

Photo: IDEE_PER_VIAGGIARE

A true war story can be nothing short of the Biblical Proverbs or Aesop’s parables. In just two short pages it can converge whole centuries of wisdom, thus proving that morality is not an abstract idea, and that just because people are at war, they don’t lose their moral code because it is innate and indispensable. The story “Enemies” strikes the reader with its genuine spontaneity. Jensen has broken Strunk’s nose and he is living in a state of constant fear. I don’t think it’s so much the fear of an eventual revenge by Strunk that festers his mind, as it is his own guilty conscience. In the end, he breaks his own nose and finally they are even.

This is a very beautiful metaphor about the balance in the universe; it harmoniously blends with the virgin nature of the Vietnamese wilderness, and it no longer seems unusual that men, occupied by war, should be thinking about justice and be tormented by guilt because of such “insignificant” quarrels. War is so much bigger than a pointless row, so much more powerful; war is everywhere around the soldiers and the sense of guilt is just in one man’s heart, and yet, for this one man the war entirely disappears and only his troubled conscience seems to matter now. This goes to show that there is something more important even than such a global event like the war – the human spirit.

For the spirit cannot be enslaved by the inevitability of war; war’s brutality cannot obliterate the power of human traits, and this is what makes the stories in the collection “The Things They Carried” almost works of poetry – the lyrical beauty of their promise that the horrors of war, no matter how great and omnipotent, cannot deprive people of their human nature; they cannot take away the feelings of love, justice and friendship from them. Ever.

Photo: Pioneer Library System

The Things They Carried is a collection of related stories by Tim O’Brien, about a platoon of American soldiers in the Vietnam War, originally published in hardcover by Houghton Mifflin, 1990. While apparently based on some of O’Brien’s own experiences, the title page refers to the book as “a work of fiction”; indeed, the majority of stories in the book possess some quality of metafiction. Even though the characters are based on a work of fiction, they show similarities of real soldiers that O’Brien knew during his time in the war.

No comments so far ↓

Nobody has commented yet. Be the first!

Comment